Riserva del

Monferrato

Beauty above and below

Discover all the excellence in this Riserva

Places & Landscapes

Places & Landscapes Culture

Culture Food & Wine

Food & Wine Craft

Craft Passionate Individuals

Passionate Individuals Industry

Industry Events

Events

The Ruby Wine

Grignolino

Grignolino is the local wine, par excellence, of Monferrato. Left aside by many during the '90s due to drops in prices, in 2006 a local wine-maker began a project aimed at rediscovering this historic vineyard - one of the oldest and most recognized varieties in the Piedmont region of Italy. Since then the success of the ruby gem, as Grignolino is also called, has prompted many other producers in the area to dedicate a portion of their production to this unique product.

With grapes selected from heritage Grignolino vines, Grignolino wine is today widely recognised as an excellent wine both representative of the Monferrato area and northern Italy. According to DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata) regulations, the grapes used in the production of Grignolino must be grown in the area of Monferrato, which is ideal for the wine’s characteristics. After harvest, the grapes undergo a long maceration process, as required by tradition, and are finally aged in barrels for 30 months.

Another DOC regulation regarding Grignolino wine requires a minimum of 90% Grignolino grapes, while the remaining 10% can be Freisa.

Grignolino’s DOC status guarantees not only a wine of superior quality, but that the wine will also meet certain characteristics, including its minimum total alcohol strength by volume of 11% and its minimum total acidity of 5.5 g/l. In addition to this, Grignolino must also have specific organoleptic properties.

Grignolino is always light ruby red in colour, the bouquet is distinctive and delicate, and the taste is dry and slightly tannic with a pleasant finish.

If you are a fan of Italian wines, Grignolino is one you definitely do not want to miss. Grignolino enhances the flavour of appetisers including mixed cold cuts and salamis and pairs well not only with fish dishes, but is also an excellent choice to accompany soups, stews, and tomato-based dishes. A tip: the ideal serving temperature for this Piedmontese specialty is between 16-18°C.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Down to Hell

Infernot

Down to Hell

Infernot

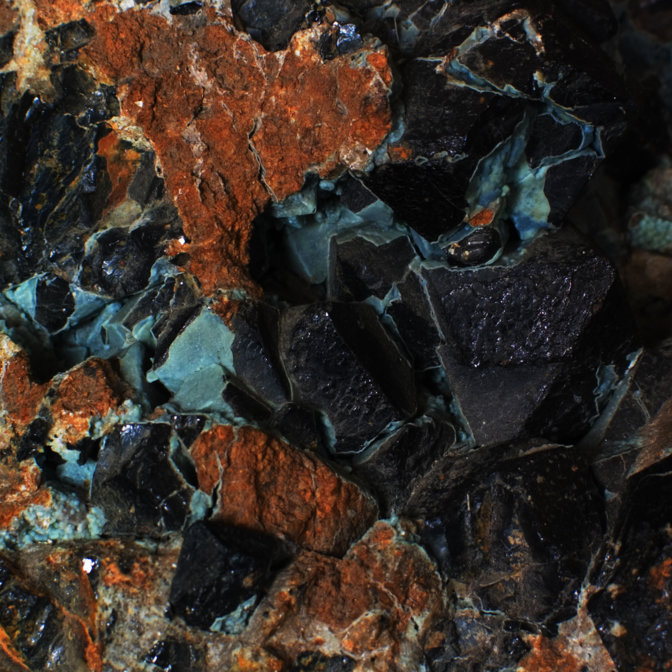

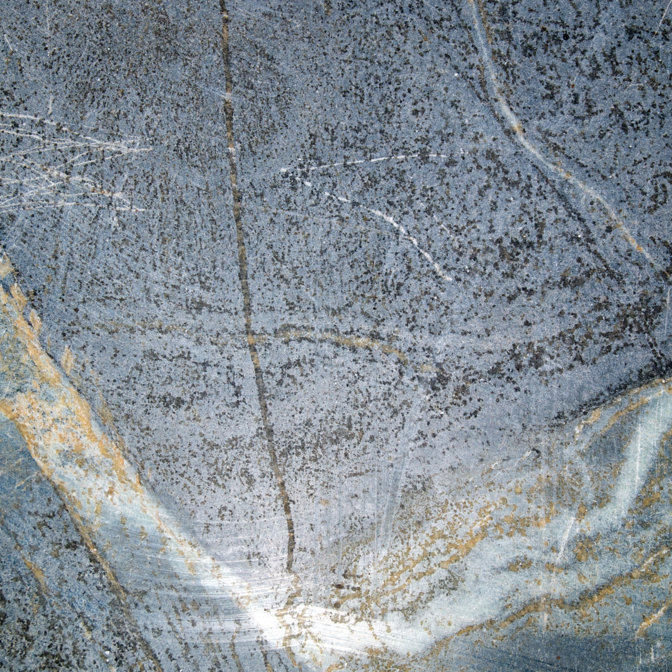

KEEPING WINE AT A STEADY, suitable temperature during hot and humid Vercellese summers was no easy matter in the past. It became customary for locals to dig wine cellars underneath their homes, carving the tuff foundation naturally present in the area at a depth of around 4 metres under the soil.

It was hard work, as it was done exclusively by hand, but it was carried out during the long and cold Piedmontese winters, when farmers were forced to a near stop due to harsh weather and low temperatures.

Hand-carving the tuff was a truly arduous job and this, in addition to the fact that these caves appeared to go very deep inside the earth, earned the cellars the name of infernot, meaning ‘small hell’ in local Piedmontese dialect.

Today, Infernot are still used to age and preserve local wines, thanks to the inimitable atmospheric properties they create.

Recently recognised as part of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the most elaborate infernot are true works of art.

A large number of the remaining infernot are part of a visitable circuit put together by the local ecomuseum, the 'Ecomuseo della Pietra da Cantoni'. Although these underground wonders deserve a visit, they aren't well-known, so if you're looking to book a tour we advise you enquire in advance.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Sin of Worship

The synagogue of Casale Monferrato

Sin of Worship

The synagogue of Casale Monferrato

The Sinagoga of Casale Monferrato, built in the Jewish ghetto in Vicolo Salomone Olper in 1595, is a monument of great historical and artistic interest. From the exterior, the building does not appear particularly art-worthy, but inside, the wealth and variety of wooden ornaments and stucco works is surprising.

The Arco Santo (Holy Arch) – where the law is preserved in precious scrolls – is bordered at the ends by two large stucco works representing the cities of Jerusalem and Hebron.

The construction of the sculpted and gilded wooden pulpit dates back to the 18th century and the enlargement of the matronaeum (women’s gallery) dates to the following century. A heavenly arch is painted on the Synagogue’s vault where, in gilded Hebrew characters, it recites: “This is Heaven’s Gate”. A permanent exhibit with works of great worth and artistic merit along with very important historical documents has been installed in the matronaeum on the first and second floor of the Synagogue.

Particularly known for its exquisite baroque interior with walls and ceiling embellished with elaborate paintings, carvings and gildings, the building was once secret.

Its plain exteriors are a testament to the past: the building, originally a clandestine synagogue, had to give no indication of its purpose as a jewish house of worship.

As in most early modern European synagogues, the synagogue was entered not directly from the street, but via a courtyard. This was done both for security reasons as well as to comply with laws requiring that the sound of Jewish worship not be audible by Christians. Originally, the synagogue’s plan was a simple, rectangular room oriented in north-south direction.

The synagogue was later expanded in the 1720s, when the ghetto was established, so as to accommodate the new Jewish population of the area. In 1823, the pavement was converted to marble and, in 1866, the main room was again expanded and a first floor was built for the matroneum.

In the years to follow, the Jewish population declined, and the synagogue with it.

In 1969, the region put into place an accurate restoration, and the synagogue was nominated as a National Monument, and is still listed as such today. Currently, the main room consists of a large rectangular space with 14 windows while the matroneum hosts the Jewish Art and History Museum, also known as the Museo degli Argenti (museum of the silvers), designed by Giulio Bourbon. On display are precious silver ceremonial objects and embroidered textiles, as well artifacts related to Jewish festivals and domestic life, such as Rimonims and Atarots. Located on the second floor is the library, with its ancient manuscripts and prayer books.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Not on My Tuff

Olivola and Moleto's Tuff

Not on My Tuff

Olivola and Moleto's Tuff

If you are a fan of lesser-known itineraries, a trip to Olivola and Moleto is the right choice if you’re in the Monferrato area.

The smallest town of Monferrato, Olivola counts less than 100 residents. Its handful of houses, though, is in a breathtaking panoramic position over an uncontaminated natural landscape.

Entirely made from tuff, the typical local material, Olivola’s houses also offer a unique chromatic uniformity.

Dominating over the town’s main square, the late-Romanesque church of San Pietro Apostolo is composed of full bricks mixed blocks of local limestone. On the edge of town, on a small hill from where you can enjoy a splendid view of the Monferrato, stands the recently restored Church of San Pietro, of Romanesque origin.

Moleto is similar to Olivola: a tiny town composed of a small group of houses set on a plateau with a breathtaking view. The village is very old and is thought to be of Saracen origin and all the houses, like in Olivola, are built in traditional tuff.

The stones from which the local houses have been built have all been extracted in the nearby quarry.

Today, the original quarry is comprised in the land of the Cave di Moleto azienda agricola, a local winery and farm on over 100 hectares.

Moleto also harbours the characteristic Romanesque church of San Michele, built before the year 1000. Constructed in blocks of tuff with a gabled façade, the church was disassembled and moved to its current location in 1968 as the original site was threatened by mining going on in the quarry.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

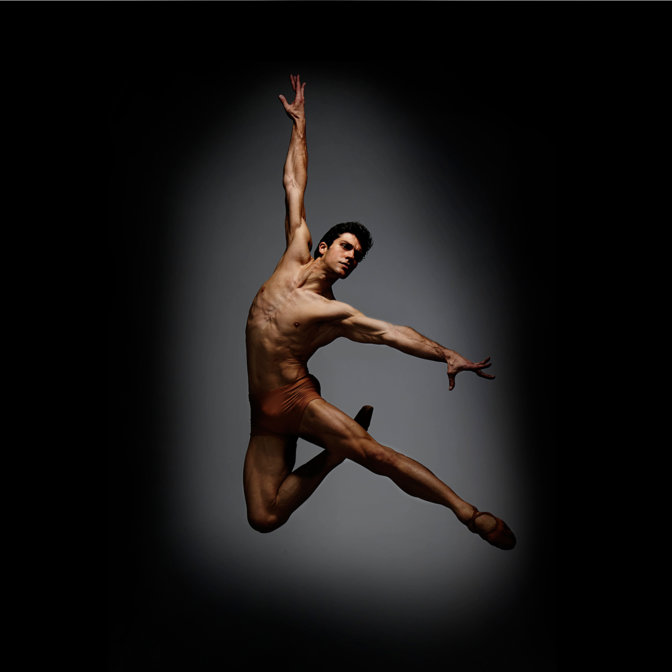

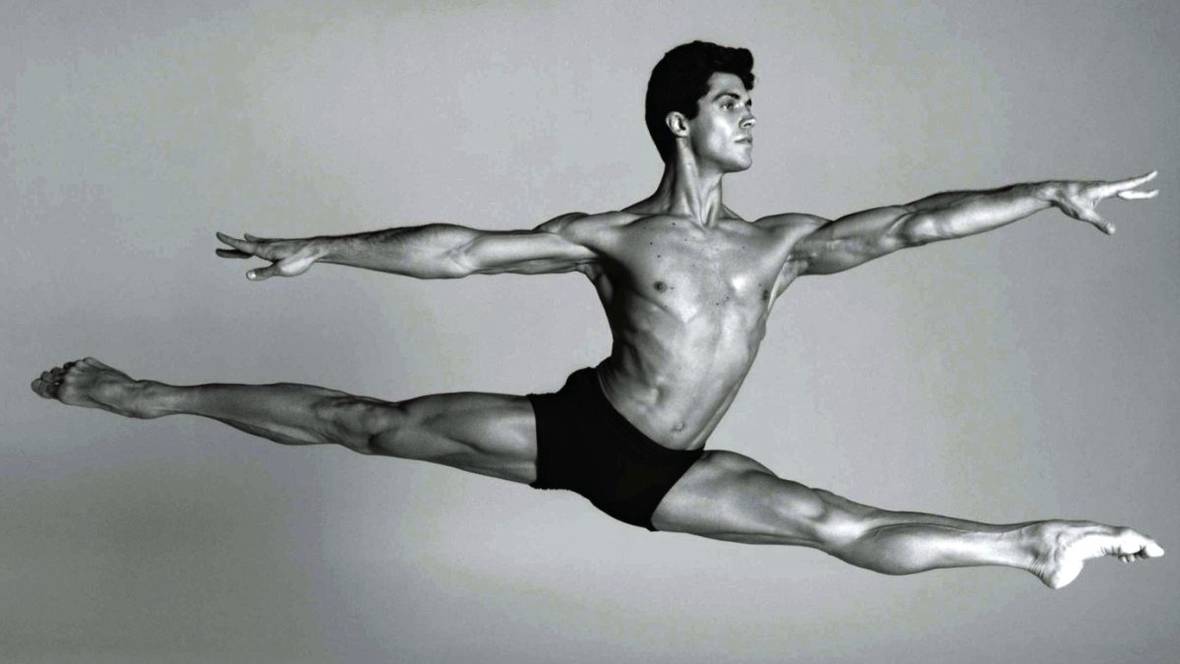

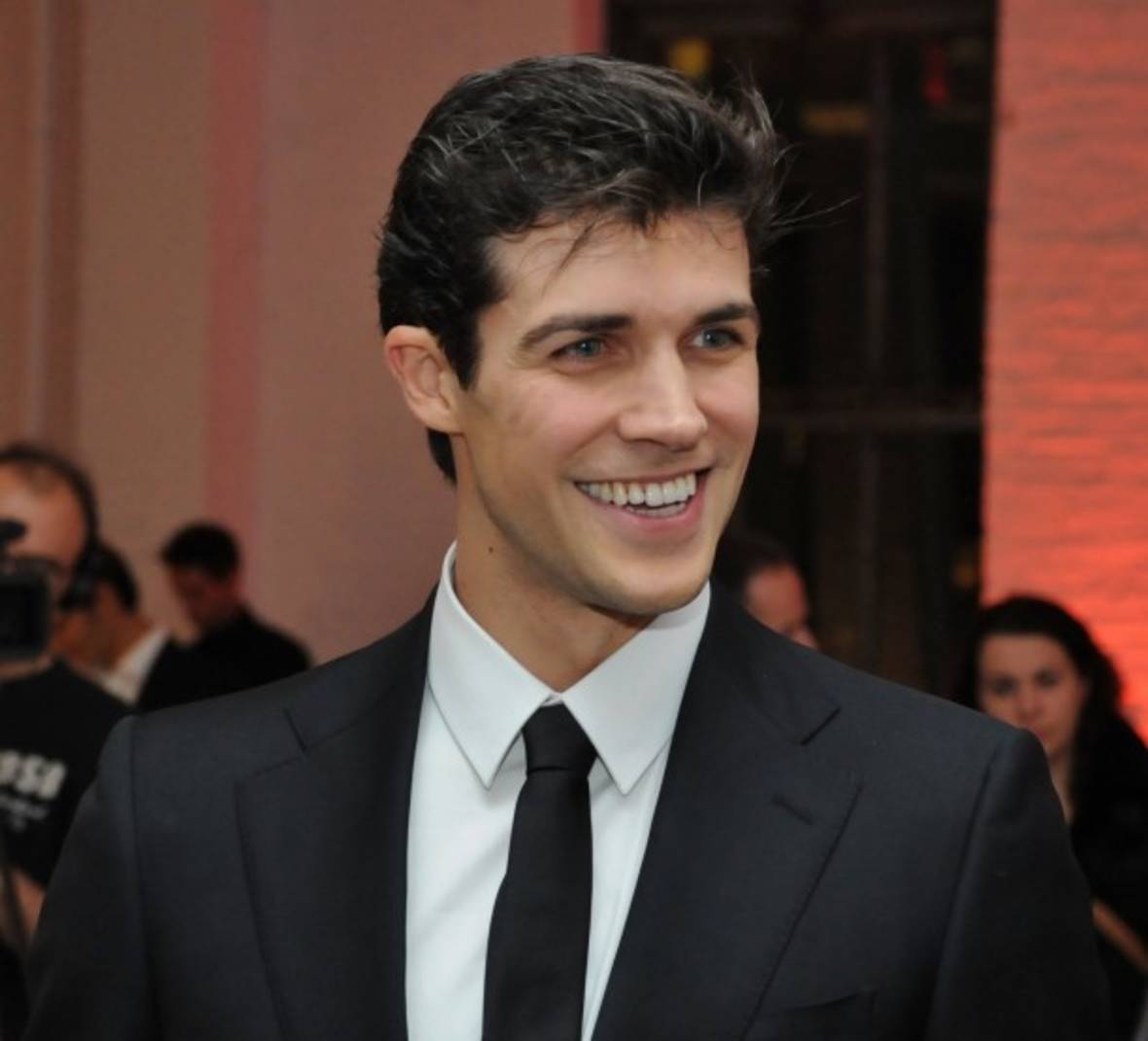

Italy's Greatest Classical Dancer

Roberto Bolle

Italy's Greatest Classical Dancer

Roberto Bolle

A world-renowned danseur, Roberto Bolle was born on March 26, 1975 in Casale Monferrato. Roberto discovered his passion for dance at a very early age; having begun ballet studies at age 7, Roberto was accepted at the La Scala theatre ballet school in Milan at the age of eleven.

At 20, after a memorable appearance in Romeo and Juliet as Romeo, he was promoted to principal dancer at La Scala by Elisabetta Terabust but left the position after only a year to pursue his career as a freelance performer.

Since then, Bolle has danced for the Royal Ballet, the Tokyo Ballet, the National Ballet of Canada, the Stuttgart Ballet, the Finnish National Ballet, the Staatsoper in Berlin, the Vienna State Opera, the Staatsoper in Dresden, the Bavarian State Opera, the Internationale Maifestspiele Wiesbaden, the 8th and 9th International Ballet Festivals in Tokyo, the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, and the City Theatre in Florence.

He has starred in many of the classics, including Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, Cinderella, The Nutcracker, Giselle and Notre-Dame de Paris.

During the 2003-2004 season, he was promoted to étoile of La Scala theatre and, in 2006, danced at the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympic Games in Turin.

Broadcast worldwide, Bolle’s solo performance during the ceremony was seen by 2.5 billion people.

Roberto’s good looks have also attracted media attention: Bolle has appeared in numerous fashion and style magazines as well as a number of important advertising campaigns. He also has an agreement with Giorgio Armani, who supplies him with clothes.

A Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF since 1999, Roberto visited many of Sudan’s schools and hospitals in 2006 and has, since then, raised over $655,000 for education and health projects in the Country.

For his contribution to Italian culture, Roberto was appointed Cavaliere dell’Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana by Giorgio Napolitano, the President of the Italian Republic, in 2012.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

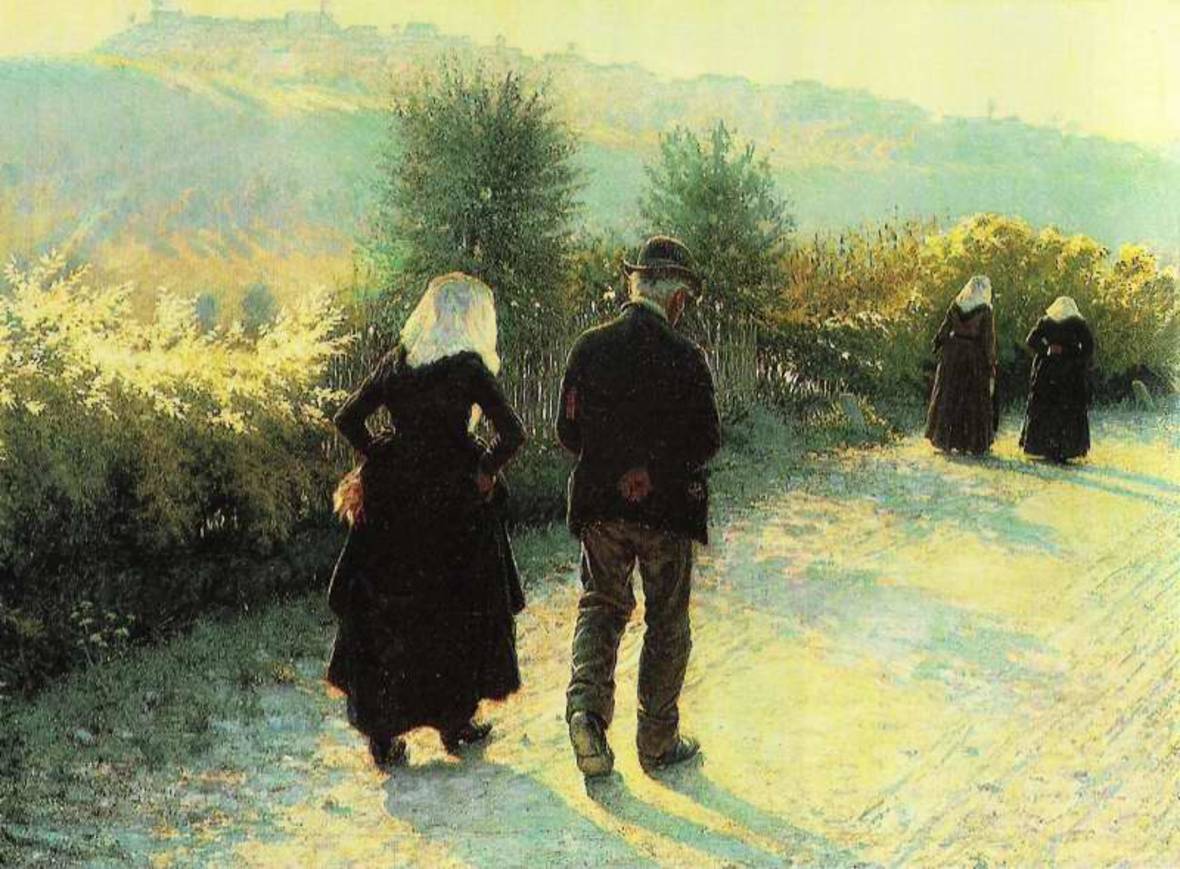

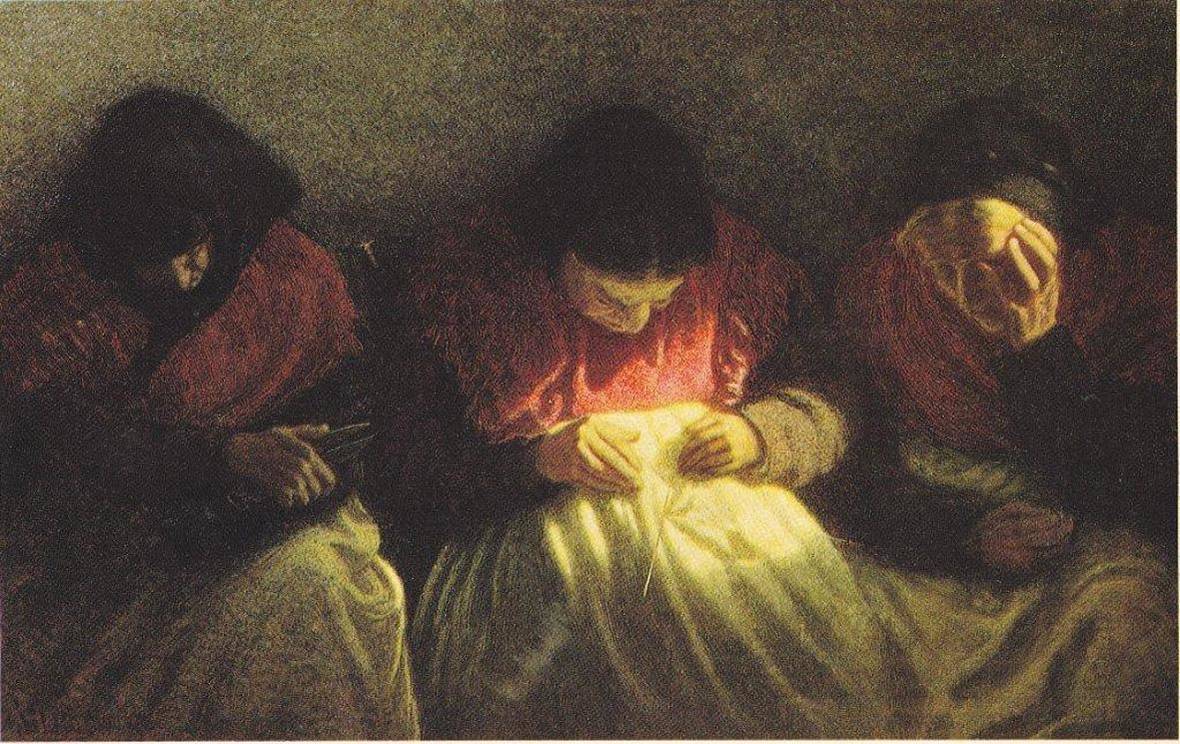

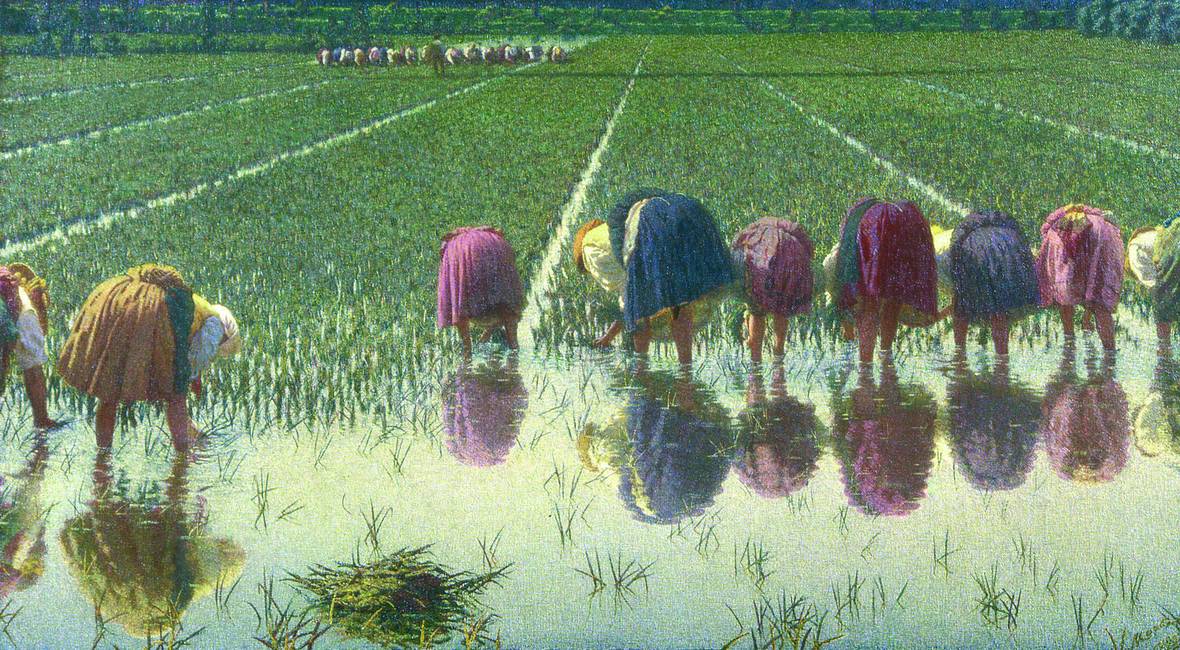

A Snapshot of Piedmontese History

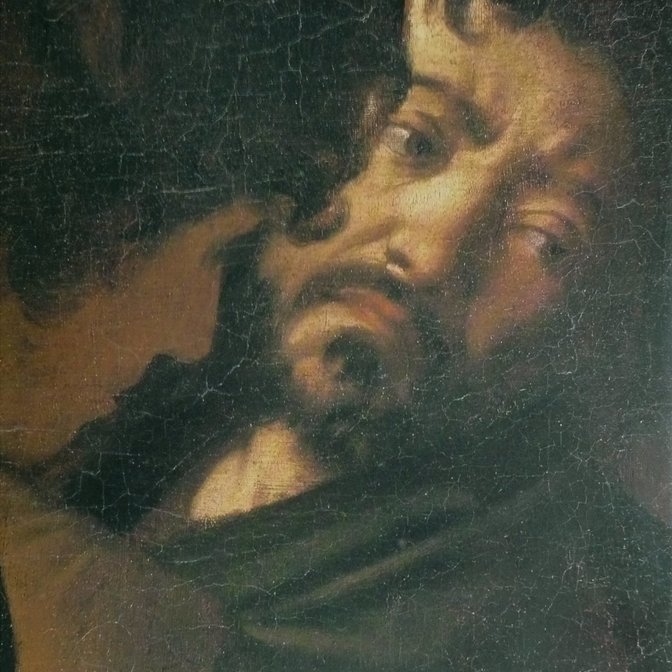

The Life and Works of Divisionist Painter Angelo Morbelli

A Snapshot of Piedmontese History

The Life and Works of Divisionist Painter Angelo Morbelli

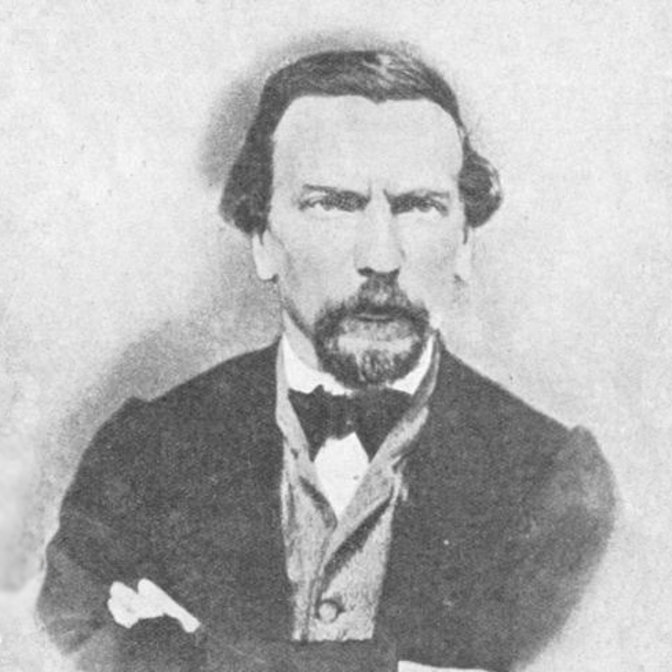

Site of the house-workshop of the divisionist painter Angelo Morbelli, Colma di Rosignano is a small village that appears as a tiny Christmas crib. Located on the southern side of the Colma hill, the village lies just under the town’s castle: the Castello di San Bartolomeo.

Here, time seems to have stopped: some of the families living in the village have surnames that date back to the 1800s, such as the Amesanos, the Angelinos, the Campagnolas and the Morbellis (Angelo’s family).

Photographs and archives, as well as Angelo’s works, tell the story of the Piedmontese countryside: traditions and activities replicated over and over again in the hundreds of towns spread over the vast northern province.

At the beginning of the 1900s, occasions of diversion were few and the patron saint's day represented the most important event for the town's people.

On the day of Saint Bartholomew, August 24th, men had the task to make the wooden ballroom platform, whereas the town’s women made the lunch of the di’ d’la festa (the Patron Saint’s day). On this occasion, relatives came from all over the county: some spent all three days of the feast’s duration in Colma di Rosignano, while others stayed just for the Sunday lunch.

The menu was the typical specialty of the village: sliced sausages and fritto misto, made up of fried liver, lungs, calf’s brains, loaves of meat and amaretti cookies. All these were followed by agnolotti filled with rabbit meat. This day was so important that a famous orchestra was called in for the occasion to play music and entertain the inhabitants. During the rest of the year, an accordion that played in the courtyard had to suffice as ‘feast’.

During normal days, the core of the village was the butega (the town store). The butega, as well as having the main features of a drugstore (you could find everything: food, tobacco, pots and pans and various household items), was an aggregation and meeting centre for women whereas, for men, it was the place where they met and played cards in the evening. To sum up, it was the ideal place to have a chat and update each other on the latest events of the community.

On Sundays, the square hosted the men’s game of bocce and all bridal processions would walk in the town’s square.

The large square situated on the top of the hill is called An s’la Curma (on the top of the Colma) for its position and shape. It gave hospitality to the main collective events: there, inhabitants lit the Carvà (the carnival bonfire) and it was there that the wooden platform for the Patron Saint’s day was built.

During the cold, harsh Piedmontese winters, activities diminished and the main commitment was looking after cattle and rmunda i sals (“to clean the willows”). Rmunda i sals was an afternoon activity and was done inside the cowsheds. The peasants prepared the willows which would have served in spring to tie the grapevines; the willows were divided into different measures (salset, sals and torci), according to their final destination.

When snow arrived, a blade with a “V” form dragged by a pair of horses served as a snowplough and cleaned all village’s streets. The village men, equipped with shovels, in a sort of game, gave their great contribution in the cleaning up.

Colma was too small of a village to host a school; for a long time, children went to school in nearby towns. They would leave the village in groups: descending towards the little chapel, they passed from house to house to call the others and little by little the group increased. The joyful company always found the way to waste time along the wide road on their way to school. In spring they looked for violets and primula flowers while in autumn they stole apples from the trees.

If it snowed during the night, the following morning one or more dads would lead the group of children with a shovel and would pave the way for the little party.

Till the end of the 60’s, the village lived on a rural reality based on small property of land: only a few families had big estates. The tilling of the land, the only source of profit for most of the inhabitants, was done thanks to the use of oxen and horses. During harvest (reaping time, the grape harvest, the haymaking and the corn harvest) people tried to help each other as there was a great need of labour and it was a time of cooperation.

During threshing, all families were engaged for several days in helping each other.

The threshing machine started its job on a farm and then moved on to the next one, day by day, from farm to farm; each member of the family played a specific role around the machine. Finally, in the evening, men debated on the quality and quantity of the corn: “this one is the best, though that one is plentiful…” Soon after, the threshing machine left the village, leaving barns more or less full, haylofts full of hay and a lot of dust.

In September, men started tidying up their basements: they washed barrels and tubs and prepared wine casks. Peasants scanned the horizon hoping for the sun. Finally, there was great animation: families and friends were all involved in the event. Yet, only a few big farms could afford the recruiting of labour by paying them. Teams of grape-gatherers sung and on the other side of the hill others answered.

Once the grape-harvest finished, it was time to harvest maize.

The barrows unloaded heaps of maize-cobs and, in the evenings, everybody had to husk the maize. Everybody sat on the heaps of maize, chatting and singing. The stripped the maize-cobs, once cleaned, were thrown near the wall of the house, where they stayed until dry.

Angelo Morbelli’s works represent this rural reality and the life of its inhabitants. Today, his workshop has been restored and is open for visits, representing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to explore Piedmontese history from its roots.

© All rights reserved.

Frassinello's Jewels

Sacchi-Nemours Castle, Lignano Castle and San Bernardo's Chapel

Frassinello's Jewels

Sacchi-Nemours Castle, Lignano Castle and San Bernardo's Chapel

With a history going back thousands of years, the town of Frassinello Monferrato boasts two magnificent castles and a baroque chapel by Sebastiano Guala.

The town’s name probably derives from the Latin fraxinus (meaning “ash”) and most likely refers to the horde of Saracens that was supposedly annihilated in the 'castro Frascenedello' (the town’s castle) in 964.

This agricultural center in the Basso Monferrato ("Low" Monferrato) is dominated by the Castle of the Counts Sacchi-Nemours and maintains traces of the defence systems and the fortress that enclosed it during the Middle Ages. The castle and the village were given as a fief to a progenitor of the Nemours family in the XIII century. This family continued to exert their control over the town for centuries and from 1787, the dynasty became Sacchi – Nemours; thus, the name of the town’s castle.

Displaying a suggestive inner courtyard and garden, the castle still displays extensive traces of the original medieval construction and the additions done in subsequent periods. The chromatic effect created by alternating white pietra da Cantoni (typical of the Monferrato area) with red bricks is the man feature of the complex.

With a 360° view over the hills of Monferrato, the castle is a true beauty if visited on a clear day; you can see as many as 32 towns as well as the Alps.

The castle’s main buildings are very scenic, with pointed arches surmounted by four turrets overlooking an italian garden.

The noble wing houses the most important rooms: the billiard room on the ground floor, the pink living room and two large rooms, the Hall of Honour and the apartment where the Nemours hosted the Bishop during his visits. Also not to be missed is the castle’s armoury, built out of volcanic rock. With an area of over 3,000 square metres, the castle’s U-shaped plan lies on a surrounding terraced park of over 5,000 square metres. Also known as the Castello di Frassinello, today the castle lets some rooms for stays and can be visited in a number of occasions.

Another fairy-tale marvel in the area is the castle of Lignano.

Built on the remains of a Roman villa, the castle gets its name from the area where it was built: a hill east of the town of Frassinello, known as the Lignano area. Dating back to the 11th century, the castle became home to the mercenary leader Facino Cane and still displays its ancient façade and cylindrical keep made from mixed stones and bricks, as well as a tombstone from the Roman period.

Today, the castle hosts a prestigious winery and counts over 115 hectares of land but its interiors still display the castle’s finely frescoed halls with the coast of arms of the Grisella family.

Every year, on Good Friday, a cortege in medieval costumes winds through the streets of the town in a Medieval representation.

If you stop by, keep in mind that the area is famous for the production of Barbera and Grignolino wines!

Tip: if you stop by, keep in mind that the area is famous for the production of Barbera and Grignolino wines!

Also noteworthy in the area: the Chapel of San Bernardo with its hexagonal layout, displaying its structure of unplastered brick and located in the open countryside.

© All rights reserved.

An Unconventional Job

The white truffle:

a Langhe & Monferrato

affair

An Unconventional Job

The white truffle: a Langhe & Monferrato affair

From September to December white truffles are harvested from their earthy homes in the hills of the Langhe and the Monferrato.

Their scientific name being tuber magnatum, white truffles are only found in specific areas of Italy, Croatia and France. However, only those from Langhe and Monferrato acquire the distinctive full, rich taste and aroma of quality white truffles, making the fungi from these small Piedmontese areas extremely prized.

One of the biggest truffles ever found weighed 1.5 kilos and sold for over $300,000.

In the past, looking for truffles in open ground was almost always carried out with special pigs, named truffle hogs. However, over the years it has become customary to use purpose-trained dogs; any dog could potentially be trained to scout for truffles but the Lagotto Romagnolo is currently the preferred breed according to trainers and truffle hunters.

Unlike female pigs, which have an innate instinct to look for truffles, dogs have to be trained and they are being increasingly used for scouting as they don’t develop the tendency to eat the expensive find! In Italy, hunting for truffles with hogs has actually even been prohibited since 1985 due to damage caused by the maladroit animals to the delicate mycelia that consent the growth of truffles.

So how does the ‘hunt’ work? Truffle-hunters, or trifolao in Piedmontese dialect, usually wake-up at around 2:30 a.m. At nighttime and dusk, the earth is cooler, and the smell of truffles is stronger. Truffle-hunters expertly search the well-known woods, accompanied by one or more dogs, until the sun begins to peep through the autumn leaves. Hunting spots are a secret that truffle-hunters hope darkness will keep!

The best spots to find truffles are under oak, hazel, poplar and beech trees.

Although truffle-farming has proven to be increasingly successful over the years, only black truffles grow on induction, while white ones can only be found in the wild. This means that truffle-rich spots are a treasured knowledge and the best locations are passed down from father to son, generation after generation of trifolao.

If you’re in Piedmont during autumn months, don’t miss the Fiera del Tartufo in Alba, Langhe, during October and November and the smaller Fiera Trifola d’Or (fair of the golden truffle) in Murisengo, Monferrato, held at the end of November.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

A Taste of the Woods

Trilobata Hazelnut

A Taste of the Woods

Trilobata Hazelnut

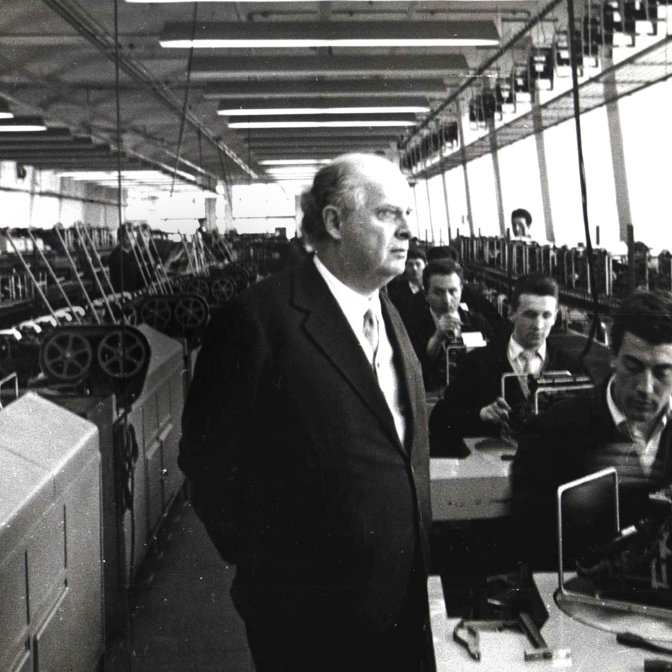

Italy is one of the world’s largest producers of hazelnuts, rivalled only by Turkey. The Piedmontese hazelnut, however, is recognised as a special variety thanks to its distinctive flavour.

The Tonda Gentile Trilobata, so called because of its perfectly round shape, is amongst the world’s best hazelnuts not only because of its delicious taste but also because it is easy to peel and can be stored for long periods without losing its characteristics.

It grows in the hilly areas of Langhe, Roero and Monferrato and is a protected I.G.P. (protected designation of origin) product, which means that the quality and the authenticity of the product are guaranteed.

Its popularity comes from the famous Gianduiotto, a chocolate and hazelnut praline invented in 1806 when cocoa had become very expensive due to import limitations imposed by Napoleon.

To reduce the amount of cocoa, chocolate makers tried to add ground hazelnut and the result was an amazing success.

Italian chocolate-maker Ferrero conquered Italy, and eventually the world, with its Nutella, an industrial version of Gianduia cream (a cocoa and hazelnut cream). Now a giant company, Ferrero doesn’t exclusively use the local crop anymore, as production is not high enough: they use about a quarter of the world’s hazelnut supply — more than 100,000 tons every year!

Today the “tonda gentile” is used for a series of high quality preparations including the aforementioned Gianduiotto pralines, Gianduia spread, Torrone, hazelnut cake and brut e bon biscuits, all delicious and very popular.

When toasted correctly, it tastes spectacular – if you get the chance, exalt its aromatic savour with a glass of rich, red wine or try to dip it in honey.

Last but not least, recent studies seem to demonstrate that, if eaten regularly, hazelnuts have a positive effect on human health. They can help maintain low “bad cholesterol” levels in the blood, and thanks to their high vitamin E content, they supply a significant quantity of antioxidant agents.

So, whether you enjoy it alone or in one of the various mouth-watering preparations make sure you try this gentle and healthy delicacy!

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Cavour's Favourite

Muletta Monferrina

Cavour's Favourite

Muletta Monferrina

Muletta translates roughly to ‘little donkey’ but, despite its name, this specialty has nothing to do with the equine world.

Muletta is a type of salami exclusive to Piedmont and is a delicacy that was appreciated, among others, by the famous Italian statesman Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour.

It represents a culinary excellence as it is an all-natural salami made from highly-selected pork meat of which only certain types of cuts such as bacon, filet, and some parts of the snout are used. The meats are cut, ground and placed in a mixer along with salt, pepper, nutmeg, wine (typically Barbera), and spices which assuredly make Muletta a specialty niche product.

The name of the salami could come from Trieste where, in local dialect, muletta means ‘girl’. Perhaps the soldiers of the wars during the Risorgimento were impressed by the women of the area as they were returning from the eastern front and, as a way of paying tribute to the women of Trieste, they decided to give the same name to this Piedmont speciality!

The origins of the name ‘muletta’ aren’t entirely clear, but various hypothesis have been made on how the Piedmontese specialty got its name.

© All rights reserved.

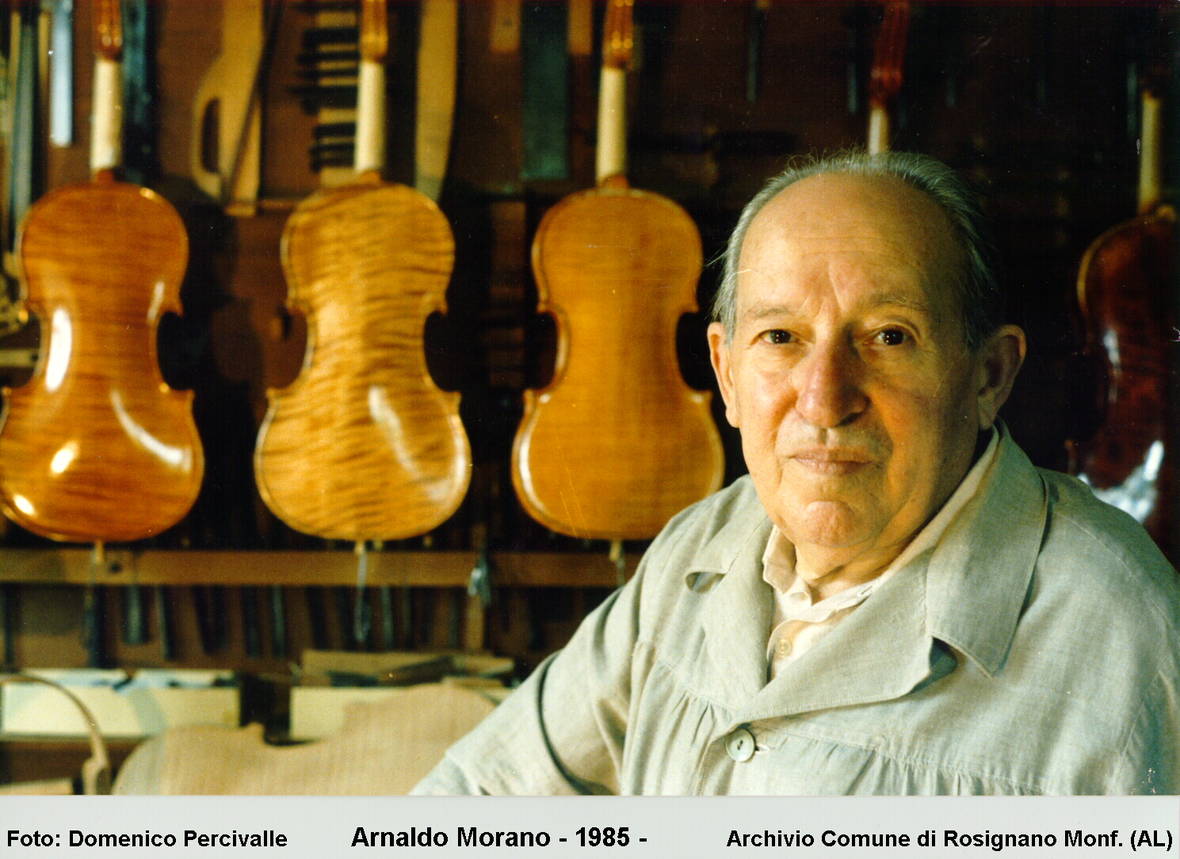

A

Master Luthier

in the Hills

of Monferrato

Arnaldo Morano

A Master Luthier in the Hills of Monferrato

Arnaldo Morano

Born in Turin in 1911, Arnaldo Morano is still considered one of Italy’s greatest violin makers. After spending the first years of his life in France, he returned to Rosignano Monferrato during the First World War. At thirteen, he started working in his father’s carpentry workshop and, having found a family violin, decided to build his own.

This first violin was only an attempt, but Arnaldo didn’t lack either ability or artistry: he knew the characteristics of different types of woods, the glues, the varnishes. Arnaldo’s first attempt at violin making became a success, considering his young age and lack of experience with musical instruments.

Arnaldo’s own hand-made violin brings him into the world of music.

Arnaldo began to study music by himself at the age of 18: at the time, music teachers were rare and very costly, and Rosignano was too far away from the big city centres of Turin, Genoa or Milan to attract any of them. Arnaldo had to learn with his own means.

His passion for luthery brought him to Turin in 1938, where he started to make new instruments and restored old ones. In the big city, he continued his musical studies and started a family. Arnaldo exhibits his instruments in Cremona in 1937 and was awarded a gold medal in the city of luthery in 1949. After having reached a certain fame in the business, he returned with his wife to Rosignano, where he opened his own workshop.

Today, his instruments are considered to be collectors’ items and are characterised by a Cremonese style and rich, orange-red varnish.

Having passed away in 2007 at age 96, Arnaldo is lovingly remembered by the people that live in Rosignano and by the world of liuthery worldwide. His house-workshop in Rosignano remains untouched and is open for visits with prior notice.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

A Twisted Idea

Krumiri Biscuits

A Twisted Idea

Krumiri Biscuits

Typical Piemontese biscuits, Krumiri are characterised by their distinctive moustache shape and fragrant taste.

Their recipe is a sweet secret and their history dates back to 1870, when the confectioner Domenico Rossi invented a new biscuit. After spending an evening with friends in his local café, Domenico invited them all to his confectioner’s kitchen and there, with a little alchemy and a touch of magic, he baked the very first Krumiri!

The origin of the name ‘Krumiri’ is not certain: some say it could come from the name of Tunisian tribes, while others claim that it derives from a liquor which was often used to accompany these cookies.

The official date of creation of Krumiri has been set in 1878: that was the year Krumiri were first advertised in local newspapers. In 1884 Domenico Rossi participated with his oddly shaped biscuits in the Universal Exhibition, held in Turin, and Krumiri proved to be a great success receiving the bronze medal.

Between 1886 and 1891, Domenico Rossi became official “Supplier to the House of his Highness the Duke of Aosta, the Duke of Genoa” and “Supplier to the Royal House of Italy to Umberto I”.

In the twenties, Angelo Ariotti took over Domenico’s business and was followed by Ercole Portinaro in 1953. In the years to follow, Krumiri gained national and international fame and began to be sold throughout the world. In 1998, after having received a selection of Piedmont’s best products, Bill Clinton even wrote a thank-you note with a special mention for the biscuits from Casale, saying they were “wonderful Krumiri!”.

Today, Krumiri are the symbol of Domenico's native town: Casale Monferrato.

Their original recipe has been patented and is characterised by simplicity and tradition. All-natural, quality ingredients are required for the rigorously hand-made Krumiri: soft wheat flour, fresh eggs, butter, sugar, pure vanilla, and, most importantly, no water. The only thing that softens the mixture are eggs and butter, giving Krumiri their special irresistible fragrance.

If you’re looking to try some, Krumiri are great on their own but their flavour is also exalted by tea, especially premier tea such as the finest Ceylon, with a round, delicate and aromatic flavour, or large-leafed Lapsang Souchong from China, naturally smoked and as light as its fragrance.

Sweet wines and liquors, too, are part of the perfect match and preferably those from the hills of the Monferrato area, where Krumiri are born.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Piedmont's Traditional Dessert

Bonet

Piedmont's Traditional Dessert

Bonet

Traditionally consumed in the colder months, bonèt is perhaps the most typical dessert of the Piedmont region, especially Langhe, Turing and the Monferrato area.

A rich spoon dessert made with amaretti biscuits, records suggest that it was served at noble banquets as far back as the 13th century.

In Piedmontese dialect, the word ‘bonet’ means hat and there are two theories as to why the dessert took on this name: the most likely reason is that it was named after the copper mould it was cooked in, shaped like a chef’s hat, but many Piedmontese will assert that its name comes from the fact that the bonèt is the last thing you eat in a meal, just as a hat is the last thing you put on before leaving a restaurant or friend’s home.

Made in a similar way to a crème caramel, the original Bonèt recipe contained only eggs, milk, sugar and amaretti cookies.

These days, everyone knows and loves the version containing chocolate and hazelnuts, which may both feature as a sprinkled or melted layer on top of the caramelized sugar or may be mixed into the custard.

The addition of chocolate to the recipe was only made possible after the discovery of the Americas, when cocoa became available in Europe, but has now largely been accepted as the traditional recipe. As a matter of fact, you probably won’t find a Bonèt without chocolate!

If you’re in the area and sit down for a good meal, of course don’t forget your hat, but also don’t forget to order Bonèt before you leave!

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

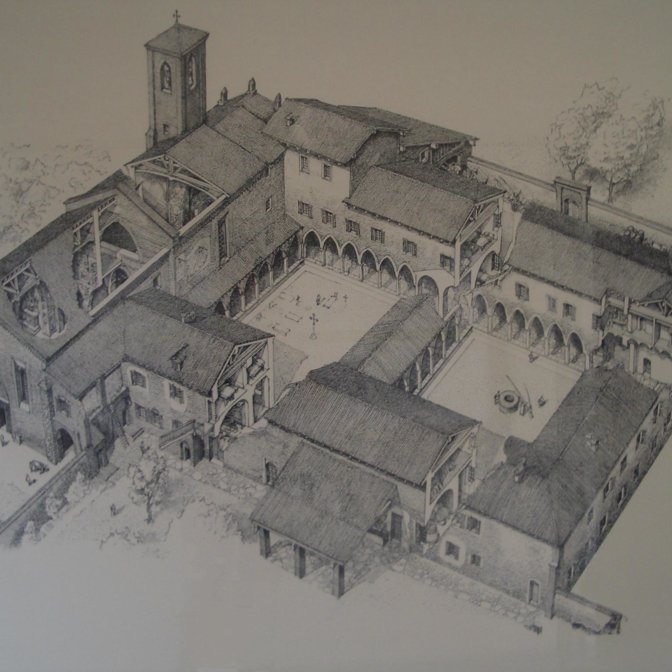

23 Chapels in a 34 Hectare Park

The Sacred Mountain

of Crea

23 Chapels in a 34 Hectare Park

The Sacred Mountain of Crea

Roman Catholic sanctuary in the municipality of Serralunga di Crea, the Sacro Monte di Crea is not actually located on a mountain, but rather on the highest hill of the Basso Monferrato. Situated 455 metres above sea level in the province of Alessandria, the beautiful location overlooking the prosperous Piedmontese plains is what has probably earned the sanctuary it its name.

Construction of the sanctuary began in 1589, around an existing religious site dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Although the creation of this sanctuary is traditionally attributed to Saint Eusebius of Vercelli around 350 AD, there is evidence that the edifice was actually built on initiative of the Prior of Crea, Costantino Massino.

It was Costantino who designed the enlargement of the pre-existing Marian sanctuary, providing also for the construction of a series of chapels dedicated to the mysteries of life and to the triumph of the Madonna.

Eusebius is also said to have installed the wooden statue of the Madonna with child, which is still venerated in the sanctuary. However, the Madonna existing today dates back to the 18th century, and little is known of its origins.

The Sacred Mount of Crea includes twenty-three chapels built in two different construction phases: one in the 16th and 17th centuries and the other in the 19th century.

Among the first chapels built are those of the Nativity of Mary and of the Presentation of Mary in the Temple. This oldest part is distinguished by complex groups of sculptures in polychrome terracotta inserted in frescoed environments, decorated by artists like Moncalvo, Prestinari and Wespin. Instead, the nineteenth century work that replaced the chapels that had been lost reveals a simpler style of statues with the exception of the chapel of the Salita al Calvario (the Climb to Calvary), in which Leonardo Bistolfi produced a composition of great emotional intensity.

The chapels, except for the first two dedicated to Saint Eusebius, are centered on different stages of the life of the Virgin.

These follow a path that culminates in the chapel of the Incoronazione di Maria (the Coronation of Mary), better known as Il Paradiso (Paradise). The Chapel of Paradise, with over three hundred statues, is the most complex of the Sacred Mount and really deserves a visit, possibly with a guide at hand to read about the history and curiosities of the different statues.

After a period of neglect following the Napoleonic suppression, the chapels were intensively restored and renovated in the course of the nineteenth century.

In 1820, significant restoration work began after the chapel’s partial destruction; this continued until the early twentieth century, and the works were carried out by Bistolfi, Brilla, Maggi, Latino, Morgari, Cabra and Rini Caironi.

Today, the sanctuary’s special setting enhances the religious building with an exceptional panoramic view over the surrounding hills and the alpine mountain chain.

Curiosity: the Sacra can be reached via a steeply ascending route which winds through a wooded natural park of 34 protected hectares, whose flora has been catalogued by the Casalese photographer and polymath Francesco Negri.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

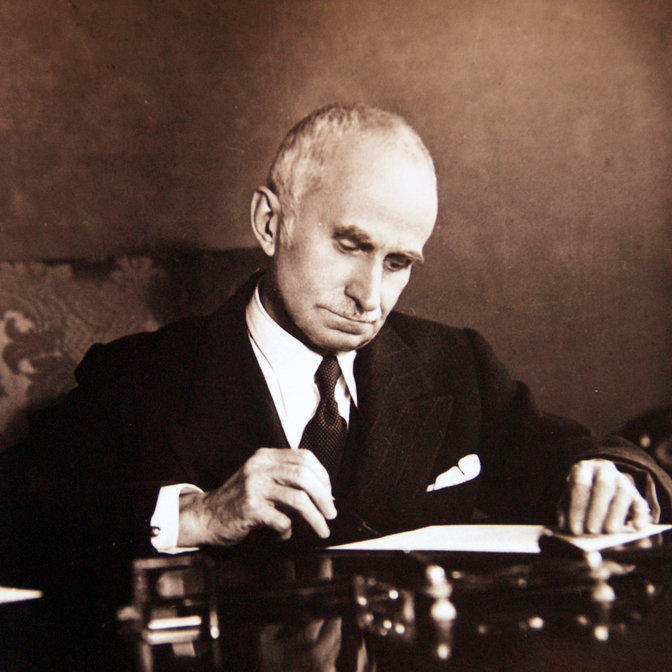

Through Highs and Lows

Casale Monferrato Castle

Through Highs and Lows

Casale Monferrato Castle

What was once a 10th century fortified housing area around the church of Sant’Evasio is today the splendid castle of Casale Monferrato. In the 14th century, Giovanni II il Paleologo, marquis of the Monferrato area, commenced the works for the construction of the castle. Completed in 1357, the castle was not built to protect the inhabitants of the area but to enable the marquis to exert control over his lands.

Originally characterised by a square plan and protected by a surrounding moat, the original edifice was modified during the 15th century, when the town of Casale obtained the title of ‘city’ from the marquis. It was then that the castle became the headquarters of the court. In this period, the castle was renovated both by Guglielmo VIII (1464-1483) and Bonifacio V (1483-1494), and some of the ancient rooms went lost during the transformations.

The 16th century was a tumultuous one for the Monferrato area: the fertile lands passed to the Gonzaga family of Mantua, and, in the same period, the last marquis of the Paleologi family died (1533). In this period, and particularly between 1560 and 1570, given the many protests and wars, the castle was fortified and its walls were thickened in response to the new military developments.

In the 17th century, the castle resumed its role as headquarters for the court.

The dukes of Mantua were frequently busy with negotiations with the House of Savoy, and often stayed at the castle. At the beginning of the 17th century, given the prolonged stays of the noble family, Vincenzo I embellished the castle with paintings and various works of art, most of which were shown in the galleria nova, which had been especially designed as show room inside the fortress.

Any suggestions?

© All rights reserved.

The Golden Truffle

Fiera della Trifola d'Or

Any suggestions?

© All rights reserved.

A Rustic Pleasure

Barbera Wine

Any suggestions?