A land of many faces, Modena and its surroundings offer a multitude of activities and stories to discover. With personalities such as Luciano Pavarotti and Enzo Ferrari, an important food and wine culture and architectural treasures that figure among UNESCO World heritage sites, this small city on the flat plains of the Po river has it all.

Discover all the excellence in this Riserva

Places & Landscapes

Places & Landscapes Food & Wine

Food & Wine Craft

Craft Passionate Individuals

Passionate Individuals Curiosity

Curiosity

Bubbles in a Glass of Red

Lambrusco wine

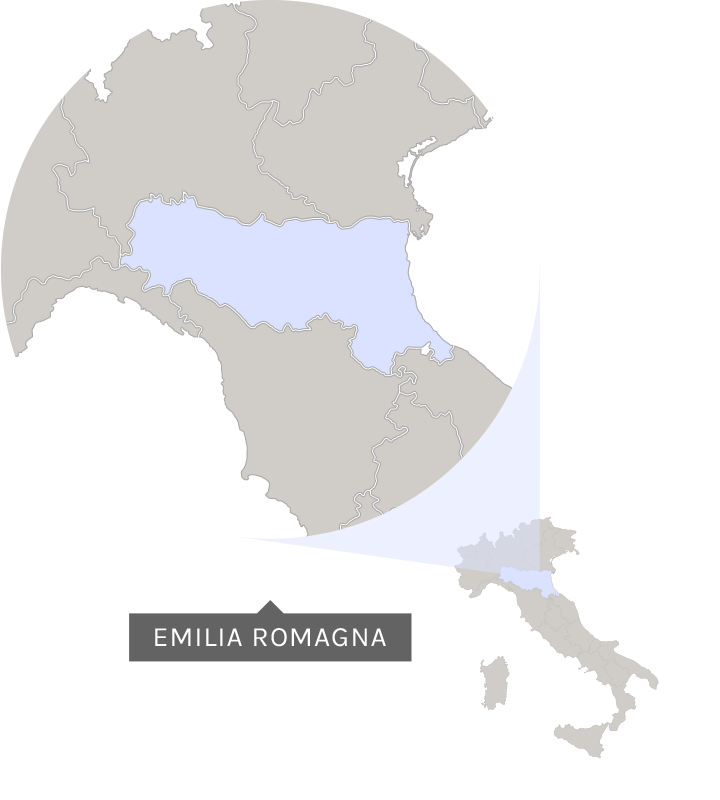

If you’re staying in Emilia Romagna and you are a wine-lover, don't leave without first having tasted a glass (ok, maybe a bottle) of Lambrusco.

A light, carefree red wine made from a grape bearing the same name, Lambrusco is indigenous of Emilia Romagna and exists in six main varieties.

White and rosé variants have been created over the years with discrete success but if you’re a first-timer, go for a glass of the original red, preferably sparkling.

Produced in the provinces of Modena, Bologna, Parma, Reggio Emilia, Mantova (Lombardy) and Trento (Trentino-Alto Adige), Lambrusco became very popular in the US during the 70′s and 80′s, especially its rosé and sweet varieties.

Slightly acidic, Lambrusco is a great accompaniment for local foods, such as parmesan cheese and cured meats, but goes well with anything slightly salty and dry. While its acidity helps to cut through the food, its bubbles help digest fatty sauces and full-flavoured foods.

A sure favourite of the ladies, Lambrusco is vivacious enough to also encounter the favours of those accustomed to fuller-tasting wines, so no excuses!

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

This Room is

a Pigsty

Pig Farming in

Emilia Romagna

This Room is a Pigsty

Pig Farming in Emilia Romagna

An undisputed authority in terms of cold cuts, Emilia-Romagna is the key Italian region for cured meat products.

Before artificial refrigeration, meat was cured to preserve it over a long period of time. Back then, animals were very precious: in peasant tradition, meat was eaten once or twice a week at the very most.

Livestock was raised independently by each family and usually consisted in hens, rabbits and, if the family was wealthy enough, a cow or a pig.

These last two were considered to be particularly fine meats. Only one per year was slaughtered, and the meat had to be somehow preserved for the months to follow. That’s why the practice of making insaccati (literally, ‘bagged’) came about.

Pig farming can be traced back to Roman times, when farming techniques were consolidated for this type of animal.

Pork and beef were preserved by being ground, spiced with pepper, salt and herbs and put into the animals’ cleaned intestines. The output (today, mainly mortadella and salami in Emilia Romagna) was then left hanging from the ceiling in a cool and airy room, in order for it to dry as quickly as possible.

Air prevented mould from forming, while cool temperatures inhibited the spread of bacteria and rotting.

Today, pig-farming remains a key sector for the area's economy and high demands have led to a spread of more intensive farming. There are still, however, a number of traditional, family-run farms that raise pigs with a higher respect of nature and animal dignity.

If you are looking to buy some of the best products of the area you could try the following shops, which still produce salumi according to tradition and using only the best ingredients:

- Pasquini & Brusiani: via delle Tofane 38, Bologna

- Scapin: via Santo Stefano 88/A, Bologna

- Franceschini: via Valle Del Samoggia 6927, Castello di Serravalle (BO)

© All rights reserved.

Tigelle for Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner

Typical Bread of Emilia-Romagna

Tigelle for Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner

Typical Bread of Emilia-Romagna

When in Emilia-Romagna you would do yourself a favour by trying the local bread, known as tigelle.

Tigelle have their origins in the mountains around Modena, the Appennini Modenesi, and are small cooked-dough discs used to accompany mortadella, salame, prosciutto crudo and other local cold cuts.

Originally, they were filled with a soft paste made from lard, garlic and rosemary; these still appear occasionally on menus in traditional restaurants. Less frequently found, but not less delicious, are tigelle filled with crescenza, a type of fresh, soft cheese typical of northern Italy.

Tigelle are served hot, yet the dough inside should be barely cooked, remaining soft and slightly humid.

Most families in Modena have a special stove for cooking tigelle, but if you have fallen in love with them and want to reproduce the recipe back home, a normal stove will do the trick just fine.

Tip: the perfect match with tigelle and cold-cuts is the local Lambrusco wine.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Say Cheese!

Parmigiano Reggiano

Say Cheese!

Parmigiano Reggiano

Parmesan, today, is a world-renowned ingredient for dainty dishes but its history goes back centuries.

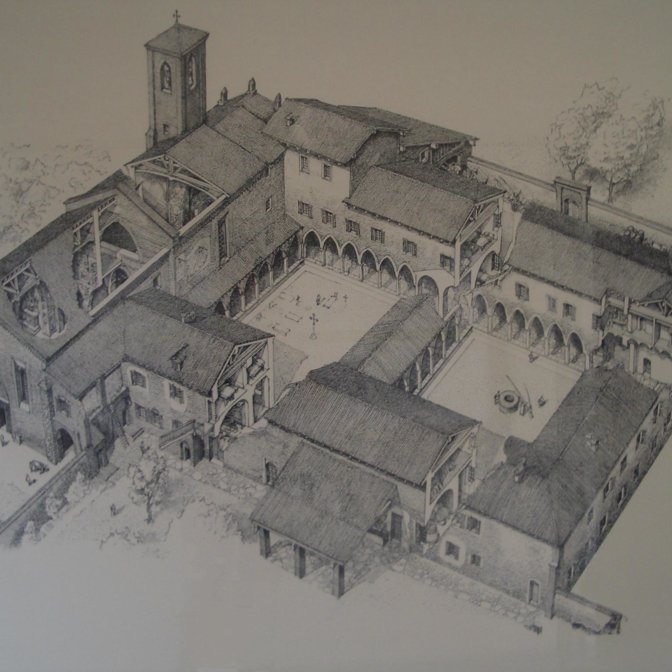

The first records of Parmigiano Reggiano appeared around 1100 a.c. when Benedictine monasteries in the restricted area of Bibbiano started producing a hard-grain cheese made exclusively from fresh, local milk.

The production quickly spread to the entire area of Reggio Emilia and the particularly tasty, grainy cheese soon became so popular that it was mentioned in Boccaccio’s Decameron (1349). The famous name derives from the cheese’s production areas, which are comprised of the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Bologna, Modena, and Mantova.

Only the cheese produced in these localities and from certified farms, which use traditional production methods, can call their product ‘Parmigiano Reggiano’.

If you’re interested to see how it’s produced, the official Parmigiano Reggiano site organises visits to certified dairies, where you will see the expert cheese masters at work. The visit is free of charge, but you must book 20 days in advance and select the area you’d like to visit. You can choose between Parma, Modena and Bologna, Reggio Emilia and Mantua.

There’s also a Parmigiano Reggiano museum in the province of Parma, with items and machinery on display dating back to the second half of the 19th century.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Drops of Time

Balsamic Vinegar

Drops of Time

Balsamic Vinegar

In Modena, balsamic vinegar is synonymous with family and traditions and written records report the existence of the precious condiment as early as 1046.

Up until the 1980s, it was common for almost every Modenese house to have its own acetaia: a cool, dark place (usually the house’s attic) in which to store the ageing vinegar.

The making process of aceto balsamico is very long, and its creation requires patience, dedication and ability.

Fresh vinegar is made from a reduction of pressed Trebbiano and grapes, which is then left to age in wooden barrels for a number of years.

Different denominations of balsamic vinegar require different minimum ageings: in order for the vinegar to be eligible for classification as Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale, for example, the minimum ageing required is 12 years. Extravecchio (‘Extra-old’) balsamic vinegar, instead, is aged for 25 years or more.

As time goes by and the water evaporates, the vinegar becomes increasingly more syrup-like. Every two to three years, the vinegar is moved to a smaller barrel, more fitting to its new concentration. The traditional ‘battery’ for the ageing of balsamic vinegar consists of 7 consecutive barrels, each one smaller than the previous one and each made of a different type of wood; this confers an incredible bouquet to the finished aceto.

To age vinegar is an act of kindness.

High quality balsamic vinegar requires such a long ageing time that many italians say you will not live long enough to taste the vinegar of your own acetaia. So be parsimonious: tasting balsamic vinegar is a must, but sparing a thought to the many years required for its creation does justice to its long-established tradition.

If you are in the Modenese area and would like to learn more about the art of producing aceto balsamico, there is a nice museum on the topic in Spilamberto, less than a half-hour drive from the centre of Modena. With a special ticket, the museum also offers the possibility to taste the sought-after vinegar. The museum is called Museo del Balsamico Tradizionale di Spilamberto and you can even take advantage of your trip by going to see the town’s 14th century castle.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

The Cherry on Top

Vignola Cherries

The Cherry on Top

Vignola Cherries

Vignola, a small town about half an hour away from the centre of Modena, is known throughout Italy for its cherries.

With its mild climate and fertile soil, the area nourished by the nearby Panaro River vaunts an established agricultural tradition, especially when it comes to cherries.

The indigenous cherry species of this area is the Moretta di Vignola, which owes its name to its dark colour.

This particular cherry type is characterised by a very sweet taste, with a lightly sour flavour at the beginning, making it ideal for cherry preserves and cherry liqueurs.

Unfortunately, the species is currently endangered and under observation, as it is slowly disappearing from local cultivation sites.

If you happen to take a walk in the Modenese countryside at the end of March – beginning of April, remember to take your camera with you: the cherry trees will be in full bloom with their white flowers. In June, Vignola will be abuzz with "Vignola... è tempo di Ciliegie" (Vignola, it's time for cherries); the annual festival dedicated to the local delicacy.

Tip: If you stop by Vignola, consider stopping at the Rocca di Vignola - the town's beautiful castle.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

A Carbon Fibre Heart

Horacio Pagani

A Carbon Fibre Heart

Horacio Pagani

HORACIO PAGANI, ARGENTINIAN BY BIRTH BUT ITALIAN BY ORIGINS, is the founder of the homonymous super-car company based in San Cesario sul Panaro, a small town just 16 km south of Modena.

Horacio’s brainchild is world renowned for its incredibly fast cars, known for their excellent aerodynamics and carbon fibre elements, which make them both light and stable.

The founder’s passion for cars came about at a very early age, with the child Horacio already shaping car models out of balsa wood.

Horacio’s obsession for perfection, too, was a trait bound to last over the years: the founder of Pagani Automobili still continuously strives for perfection, in accordance with Leonardo Da Vinci’s principle of combining art and technique.

At the beginning of his career, Pagani moved to Italy from Argentina and started working for Lamborghini, later opening up the Pagani Composite Research for studies on carbon fibre. This first company contributed to the creation of a number of Lamborghini cars, including the Diablo, the Lamborghini P140, the L30 and the Diablo Anniversary.

After years of experience alongside Lamborghini, Horacio decided to fulfil his dream of building his own super-cars and opened Pagani.

Horacio designed, engineered, modelled and moulded prototype cars for his Pagani Automobili, which, at its birth, was almost a one-man company.

His first prototype was to be the Fangio F1, which, in 1993, was already being tested at the Dallara wind tunnel. A year later, Mercedes Benz agreed to power Pagani with V12 engines. Juan Manuel Fangio unfortunately died in 1995 and Horacio decided to change the name of his first car as a sign of respect. The car became Zonda C12, named after an air current which flows in the Andes.

The Zonda, inspired by jet fighters, features several unique design elements, including its circular four pipe exhaust.

In 2010, a Zonda tricolore was announced, of which three models were eventually made. The car was created in honour of the Italian Air Force’s aerobatic squadron, the Frecce Tricolori (‘the tricoloured arrows’, with the tricolour being the name of the Italian flag).

The Pagani Huayra, named after the Incan god of wind, made its grand debut in 2011 and is the successor of the Zonda. Its main body is made from carbontanium, a mix of carbon fibre and titanium. Its top speed reaches 235 mph (378 km/h) and its 0–100 km/h time is a mere 3.2 seconds.

Should you wish to learn more about Horacio’s dream, the Pagani factory and show room are open for visits upon request.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

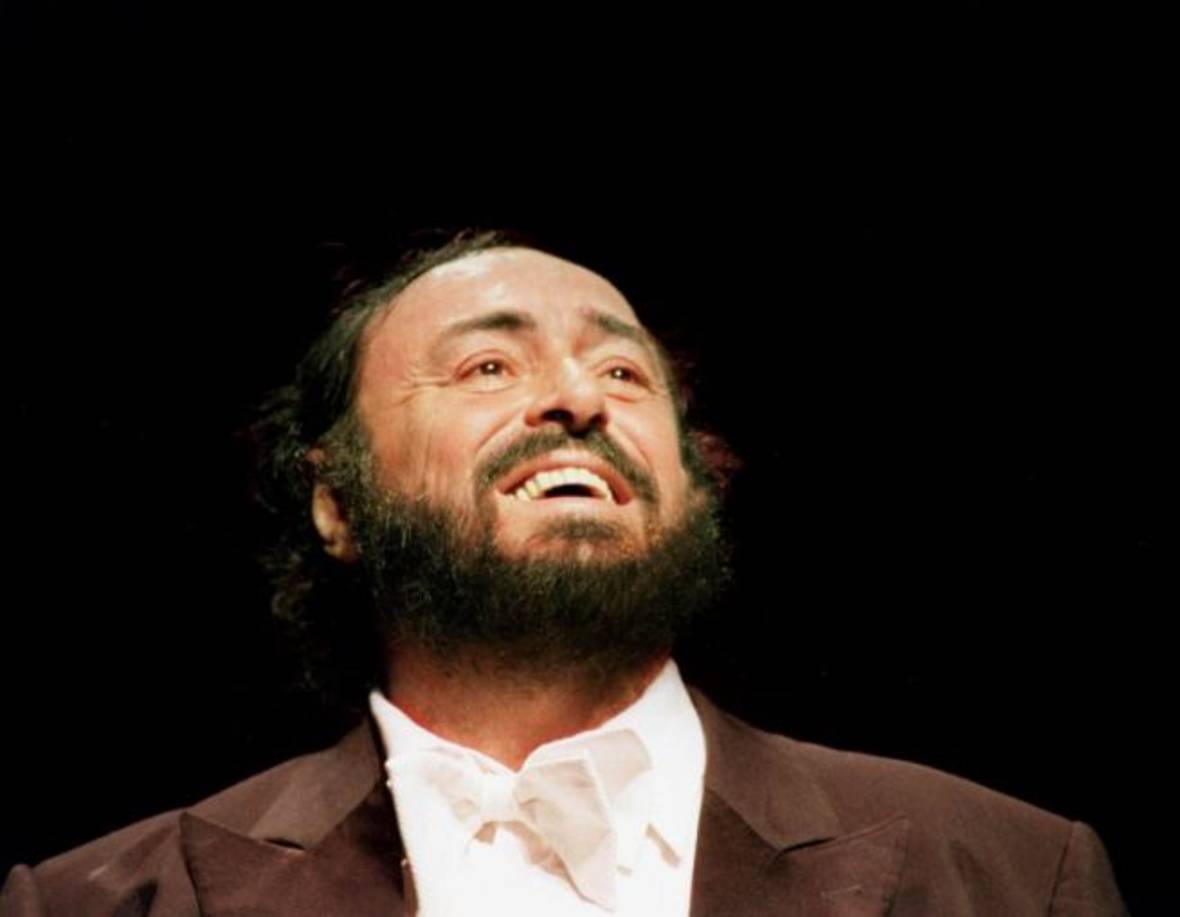

Big Luciano

Luciano Pavarotti

Big Luciano

Luciano Pavarotti

Luciano Pavarotti was one of the most loved figures in Italian musical history. Although his musical genre could, by no means, be defined as easy or popular, many were inspired to learn more about the opere classiche thanks to his voice and stage presence.

A native modenese, Pavarotti was born from a working-class family in 1935. His father was an amateur tenor, but never gave public performances due to his nervousness. His recordings, however, served as an inspiration for the young Luciano, who started taking singing classes and began attending a church choir. Growing up, he started working as a teacher in elementary school but, after two years, decided to dedicate himself to music, taking singing classes from a professional tenor from Modena.

Pavarotti’s first appearance outside Italy took place in 1963, playing a role in La Traviata in Belgrade, Yugoslavia.

The beginning of his career, however, did not immediately propel Pavarotti to international recognition. Nevertheless, 1972 proved to be a crucial year in pavarotti’s career: performing at the new york’s metropolitan, he won the audience’s undivided admiration and received an astounding 17 curtain calls.

In the 1980s, the world-class tenor set up an international competition for young singers, where the winners would perform with him at various international events. In 1990, his Nessun Dorma by Giacomo Puccini became world-famous when the BBC used the aria as the theme song for that year’s coverage of the FIFA World Cup, and the song soon became the singer’s trademark. The day before the end of the World Cup, Pavarotti also sang with Plácido Domingo and José Carreras in a concert held in the Baths of Caracalla (Rome).

‘The Three Tenors’ Concert’, as the performance was named, became the biggest selling classical record in history.

His fame, however, was not always accompanied by compliments. Pavarotti frequently cancelled concerts and appearances and this earned him the name of ‘King of Cancellations’ and resulted in poor relationships with some of the most important opera houses in the world.

The end of Pavarotti’s career coincided with his ‘Farewell Tour’: he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2006 and had to suspend the tour to undergo major surgeries. Although he had made plans to resume the tour, he passed away in his house in Modena a year later.

As Italians, we like to remember him as the man with the big voice who, thanks to his musical and ethical greatness, helped countless national and international humanitarian causes.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

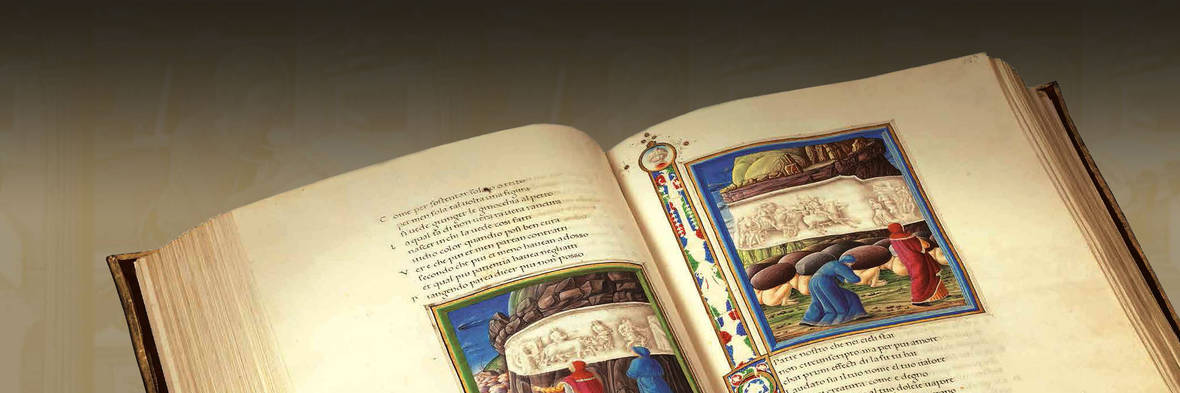

The Work of a Lifetime

Illuminated Manuscripts of Castelvetro

The Work of a Lifetime

Illuminated Manuscripts of Castelvetro

If you are out on a trip around Modena and you happen to stop by the beautiful medieval town of Castelvetro, take a walk to the central square and follow the road that leads to the town’s castle.

On your right, you’ll find a shop named ‘Art Codex’: take a look inside. Here, specialised artists bring the most important illuminated manuscripts of the past back to life, creating stunning high-fidelity reproductions. Even if you are no connoisseur of the genre, the stones, the colours and the atmosphere are will leave you breathless.

Manuscripts were the only mean of reproducing a document or a book before the arrival of woodblock printing and the printing press; they were traditionally reproduced by monks. In those times, the majority of the population was illiterate, except for the clergy. In fact, part of the strict formation to enter the monastic order included Latin and, sometimes, ancient Greek.

Copying a manuscript was an extremely long job and required a lot of patience.

Monks lived in isolation and frequently dedicated their days to manuscript writing. Many would devote their entire lives to copying a single book. And often, this would not even suffice: several works have two or three copyists as a new monk would take over the unfinished job of his predecessor.

Today, only few manuscripts survive, partially due to the disastrous fire that destroyed the library of Costantinopole, along with its precious works, in 1204.

The few remaining manuscripts are an incredibly valuable testimony of the past and even their study can compromise their preservation. Manuscript details, techniques and materials have been the object of many years of study by Art Codex’s creator, Luciano Malagoli. His reproductions have been used by historians as substitutes of the original texts, carefully preserved in libraries worldwide. Thanks to his high-fidelity creations, original manuscripts are preserved from sunlight, use and general damage while the history of illuminated manuscripts and their secrets can still be unveiled.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

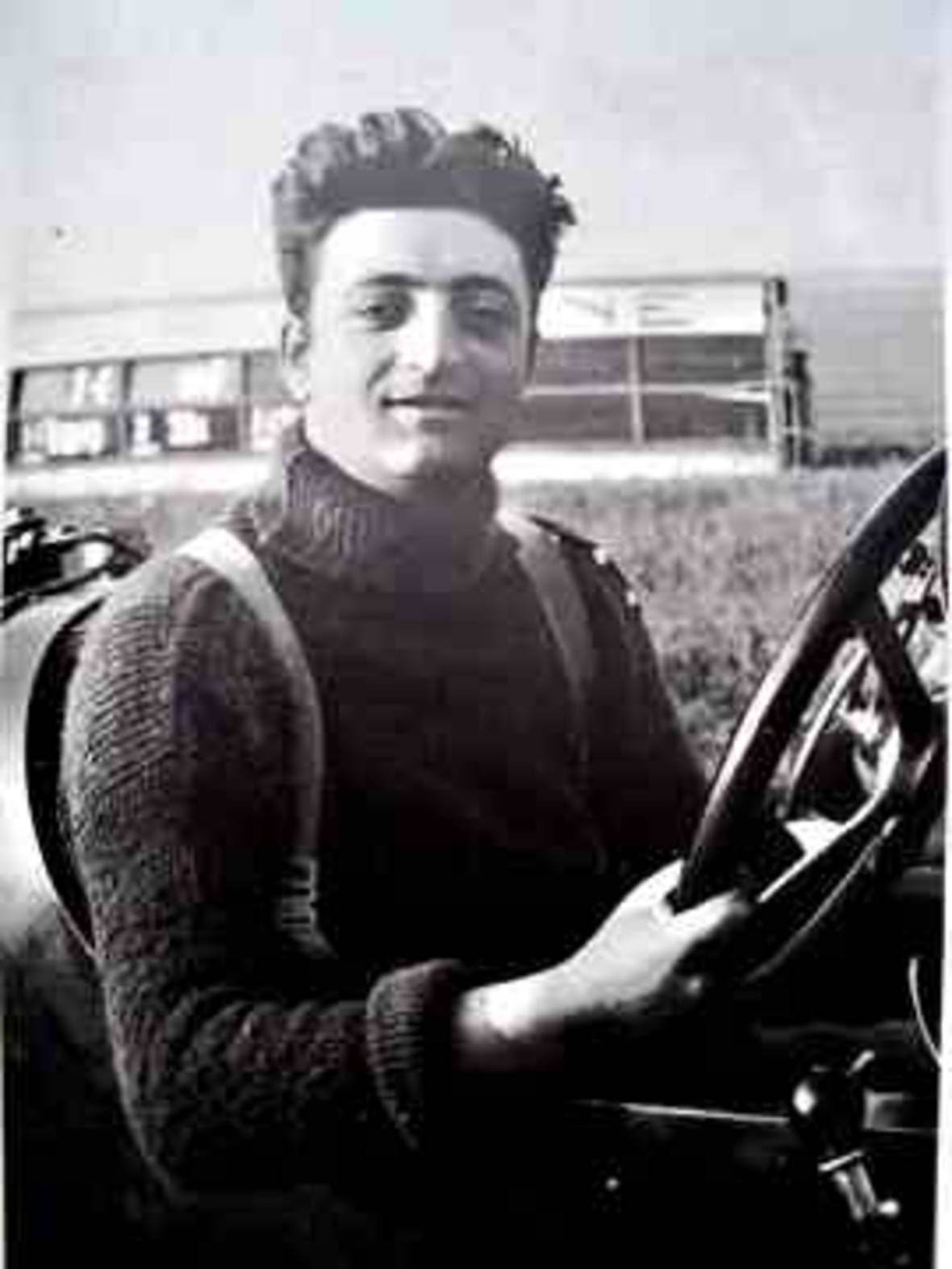

The Father of Modern Racing

Enzo Ferrari

The Father of Modern Racing

Enzo Ferrari

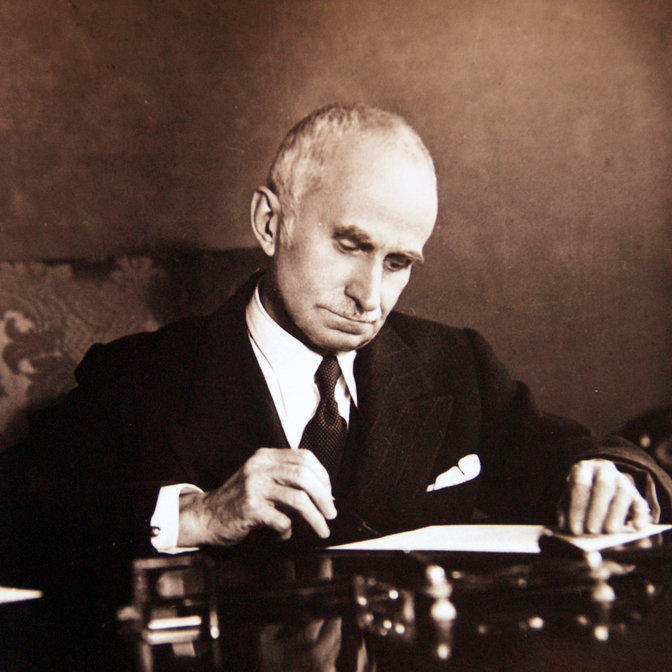

Enzo Anselmo Ferrari was born on the outskirts of Modena on the 18th of February 1898, a day that changed the racing world forever.

At the age of ten, Enzo and his brother Alfredo were taken by their father to watch a race at the motor racing circuit on Via Emilia in Bologna. The race was won by Felice Nazzaro and the young Enzo was completely entranced by the action.

Unfortunately, Enzo’s happy days as a child came to an abrupt end in 1916, when the family was hit by a double tragedy: both Enzo’s father and brother passed away in a matter of months. Enzo was forced to give up his studies after his father’s death and found work as an instructor in the lathing school at the fire service workshop in Modena.

During the First World War, Enzo served in the Italian army in the 3rd Alpine Artillery Division. However, he became seriously ill and had to undergo two operations before being honourably discharged.

On the road to recovery, Enzo attempted to get a job with Fiat in the northern city of Turin, but to no avail.

A year later, he found work as a test-driver for a small company in Turin that built the much sought-after Torpedos. In 1919, Enzo moved to Milan to work for C.M.N (Costruzioni Meccaniche Nazionali), first as a test-driver and then as a racing driver.

Enzo makes his competitive debut in the 1919 Parma-Poggio di Berceto hillclimb race in which he finished fourth in the three-litre category at the wheel of a 2.3-litre 4-cylinder cmn 15/20.

On November 23rd of the same year, he took part in the Targa Florio but lost by over 40 minutes after his car’s fuel tank developed a leak. In 1920, after a series of races in which he enjoyed mixed fortunes at the wheel of an Isotta Fraschini 100/110 IM Corsa, Enzo finished second in the Targa Florio in a 6-litre 4-cylinder Alfa Romeo Tipo 40/60. This marked the start of a 20-year collaboration with Alfa Romeo in which Enzo would finally be appointed as head of the Alfa Corse racing division.

In 1921 Ferrari competed in several races as an official Alfa driver, delivering some impressive finishes, such as fifth position in the Targa Florio in May and second at Mugello in July. He also had his first major accident in September that year when he went off the road on the eve of the Brescia Grand Prix, trying to avoid a herd of cattle blocking the race route. In 1923 Ferrari won the first Circuito del Savio and met Count Baracca, father of the famous Italian First World War pilot Francesco Baracca. He later met Countess Baracca who gave him a signed photograph and invited him to use her son’s Prancing Horse emblem as a mascot on his cars.

In 1924 Enzo Ferrari was made a Cavaliere (Knight) for his sporting achievements, his first official honour from the Italian state.

He was made a Cavaliere Ufficiale in 1925 and his passion for journalism saw him become one of the founders of the famous Corriere dello Sport newspaper in Bologna that same year. In 1927 he was made Commendatore by the Italian state in recognition of his services to the Nation in the area of racing. On June 5th of the same year, he won the first Circuito di Modena in an Alfa Romeo 6C-1500 SS.

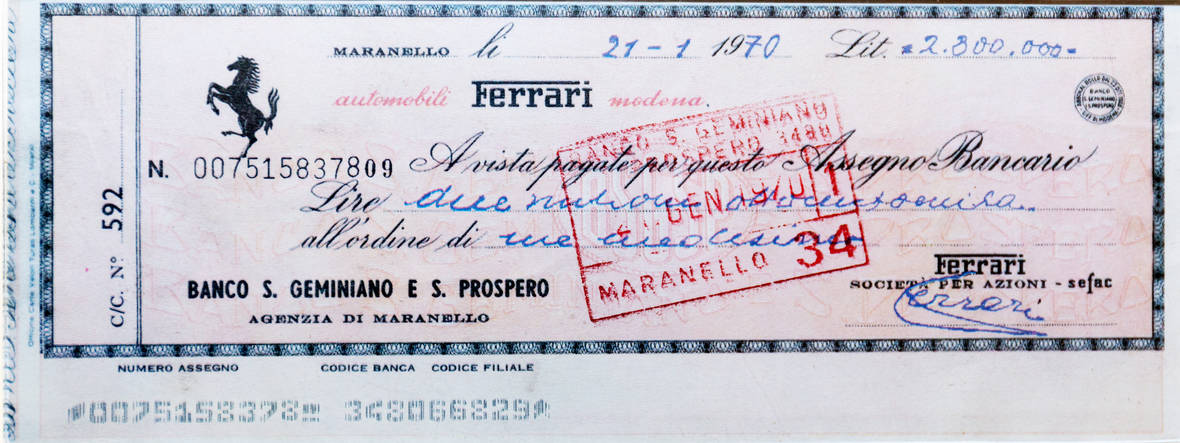

In 1929, Ferrari founded the Scuderia Ferrari in Modena.

His main aim was to allow owner-drivers to race. The foundation of the Scuderia marked the start of a burst of frenetic sporting activity that would lead to the creation of an official team. The Scuderia fielded both cars (mainly Alfas) and motorbikes and, in time, it became a technical-racing outpost of Alfa Romeo and effectively took over as its racing department in 1933.

In 1931 Enzo Ferrari completed his final race as a driver at the Circuito Tre Province, finishing second to Nuvolari in an Alfa Romeo 8C -2300 MM. The decision to quit racing came as result of the impending birth of his son Alfredo, better known as Dino (19th January 1932), and his growing workload as head of the Scuderia.

In 1937 the Scuderia Ferrari built the Alfa Romeo 158 “Alfetta” which went on to dominate the international racing scene and, at the beginning of 1938, Enzo Ferrari took up his new position as head of Alfa Corse and moved to Milan. On September 6th 1939, Enzo left Alfa Romeo under the provision that he did not use the Ferrari name in association with races or racing cars for at least four years.

From that moment on, beating Alfa Romeo in one of his own cars became a personal passion for Enzo.

On September 13th he opened Auto Avio Costruzioni on Viale Trento Trieste in Modena, the headquarters of the old Scuderia Ferrari. Auto Avio Costruzioni built two versions of what Ferrari called the 815 (8 cylinders, 1500 cc) on a Fiat platform for the last pre-War Mille Miglia: they were driven by a young Alberto Ascari and Marquis Lotario Rangoni Machiavelli of Modena but fail to shine. At the very height of the War in 1943, Auto Avio Costruzioni moved out of Modena to Maranello where the first part of what would later become the Ferrari factory was built. A year later, on November 4th the factory was bombed. Hit again the following February, it was quickly rebuilt.

Enzo began work on designing the first Ferrari in late 1945: his ambitious plan was to power it with a V12 engine.

In fact, this particular architecture would become a fixture throughout the company’s entire history. The reason Ferrari chosen a V12 was its versatility: it was just as suited to use on sports prototypes as single-seaters and even Grand Tourers. At the end of the following year, Ferrari released specifications and drawings of his new car to the press.

On March 12th, 1947, he took the car, now known as the 125 S, out for its first test-drive on the open road. Having won its first Mille Miglia in 1948, its first Le Mans 24 Hour Race in 1949 and its first Formula 1 World Championship Grand Prix in 1951, Ferrari became world Champion for first time in 1952 thanks to Alberto Ascari who repeated his feat the following year. 1952 was also the year Enzo Ferrari was made Cavaliere del Lavoro in recognition of his services to industry and to enhancing Italy’s international reputation.

In 1956, Enzo’s beloved son, Alfredo, or Dino as he was better known, died of muscular dystrophy. Ferrari had kept his son involved in the design of a new 1500 cc V6 until the very end of his life. The engine finally debuted 10 months after Dino’s death: all Ferrari V6 engines are named in his honour.

In 1960 Ferrari became a Limited Liability Company and Enzo was conferred with an Honorary Degree in Mechanical Engineering by Bologna University. 1963 saw Enzo build the professional industry and artisanship training institute in Maranello. Dedicated to Alfredo “Dino” Ferrari, it continues to provide the company with special technicians to this day.

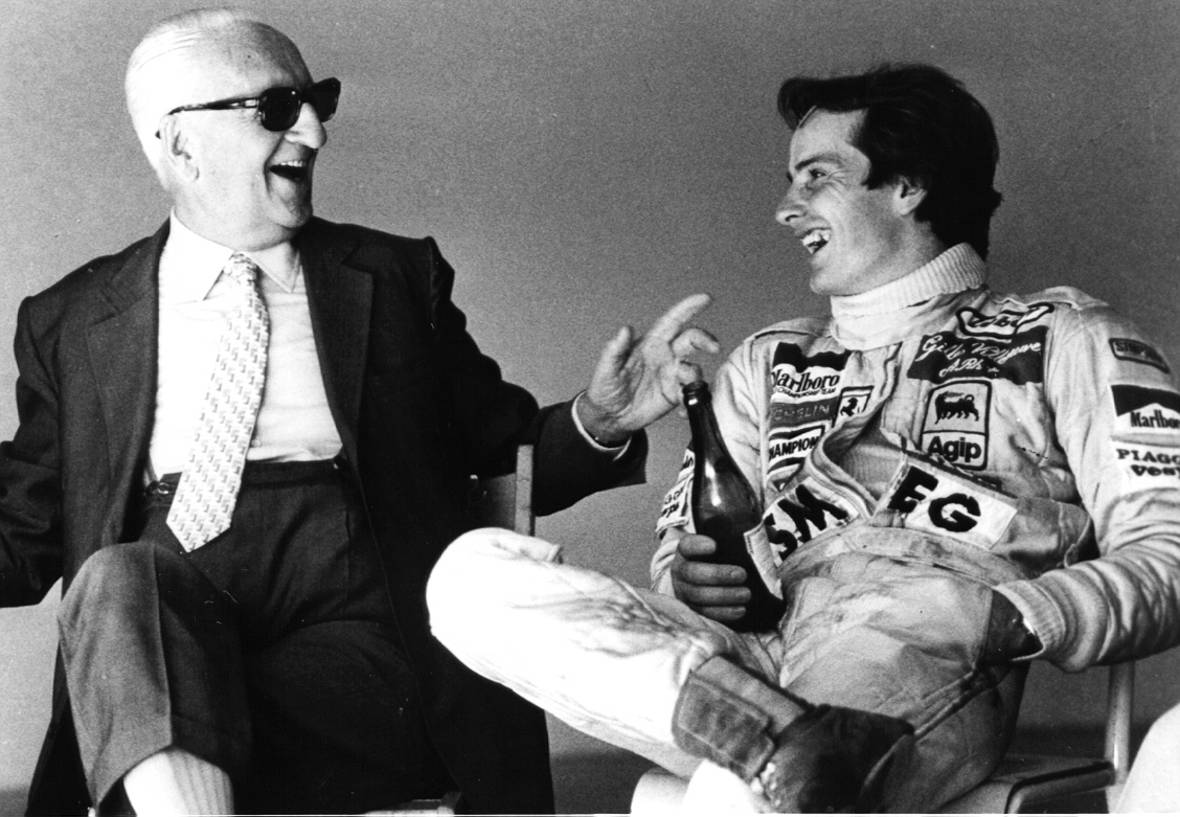

As time went by, Enzo became aware that he required a powerful partner if the company was to continue to develop: in 1969 he signed an agreement with the Fiat Group giving it a 50% stake in the company shares. In 1970 Enzo was presented with the Gold Medal for Culture and Art by the President of Italy and started to build the Fiorano Circuit, which would be officially opened on April 8th, 1972. In 1979, Ferrari received the honorary title of Cavaliere di Gran Croce della Repubblica Italiana from Pertini.

The F40, the last car to be created under Enzo's management, was unveiled in 1987. Enzo sadly passed away in 1988, at the age of 90. It was the same year he was conferred an honorary degree in physics from the University of Modena.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

Out to discover Modenese Castles

Out to discover Modenese Castles

If you are passionate about Medieval buildings, the castles around Modena are an ideal destination for a day trip. There are many to choose from and a complete list can be found on the Castelli di Modena site, but here we have hand-picked a variety of our favourites for you to browse. Beware that, as a consequence of the severe 2012 earthquake that hit the Modenese area, many castles have been closed off to the public for safety reasons. Check with the local administration if full or partial visits are possible.

In our opinion, the most relevant ones in terms of conservation and architectural complexity are:

- The Castello di Vignola: a stunning Medieval castle, not to be missed even by those who are not fans of the genre. While in the area, have a taste of the delicious local cherries;

- Castello di Castelvetro, a 9th century castle in a beautiful old-town setting, perfect for an afternoon visit followed by an aperitivo at sunset in the town square;

- Castello di Formigine, the visit of which should be followed by a stroll inside its beautiful park;

- Castello di Spilamberto, worth a stop especially if you're already out to see the balsamic vinegar museum in the same town;

- Castello di Sassuolo, this last one missing from the Castelli di Modena list, but beautifully frescoed and with a distinctive noble allure.

If you don’t mind travelling a bit further afield in search of Medieval treasures, here are two combinations you can visit: the Castello di Montecuccolo in Pavullo nel Frignano, is just under an hour's drive from central Modena and is absolutely beautiful. If you are really enjoying the Modenese countryside, get back in the car and stop by the Castello di Roccapelago, in the town of Pievepelago. The Castello di Roccapelago is 50 minutes from Pavullo nel Frignano and about an hour and a half from Modena itself.

Another duo is that starting with Palazzo dei Pio, in Carpi: the edifice is more of a noble palace than a castle, but it is usually included among local castles. It's in an area with fewer things to see, so if you go there on purpose, you may also wish to see Castello Campori, in Soliera, about 10 minutes from Carpi.

Any suggestions?© All rights reserved.

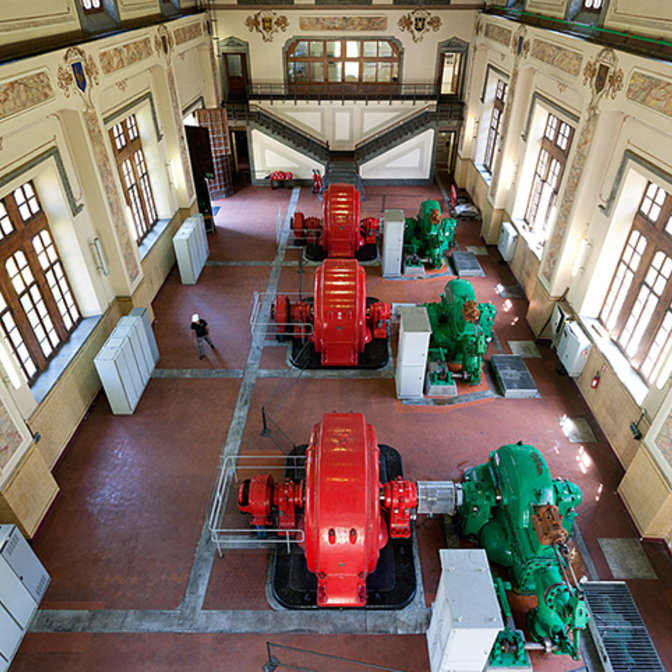

Ferrari

Ferrari

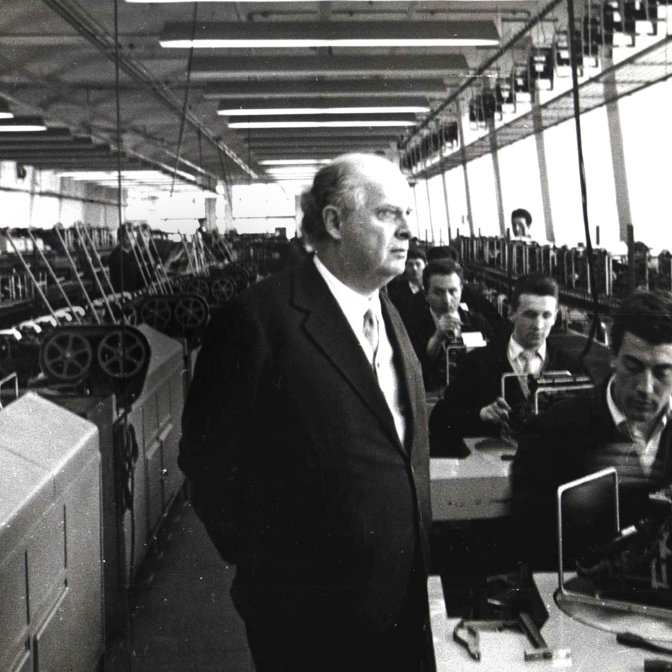

For car-lovers, the treasure that Maranello jealously cradles, needs no introduction. Born in 1947, Ferrari has always produced its dream vehicles at its current site, just a few kilometres away from Modena.The company’s story officially began when the first Ferrari emerged from the historic factory entrance on Via Abetone Inferiore in Maranello: the 125 S, as it was known, embodied the passion and determination of the company’s founder.

Enzo Ferrari was born in Modena on February 18th, 1898 and died on August 14th, 1988. He had devoted his entire life to designing and building sports cars and, of course, to the track. Made an official Alfa Romeo driver in 1924, within five years he had gone on to found the Scuderia Ferrari on Viale Trento Trieste in Modena. In 1938, Enzo Ferrari was appointed head of Alfa Corse but quit the position in 1939 to set up his own company, Auto Avio Costruzioni, which operated out of the old Scuderia buildings. This new company produced the 1,500 cm³ 8-cylinder 815 Spider, two of which were built for the Mille Miglia in 1940.

All racing activities ground to a halt, however, with the outbreak of the Second World War.

In late 1943, Auto Avio Costruzioni moved from Modena to Maranello. The end of the war saw Ferrari design and build the 1,500 cm³ 12-cylinder 125 S, which made its competitive debut in the hands of Franco Cortese at the Piacenza Circuit on May 11th, 1947. On the 25th of the same month, it won the Rome Grand Prix at the city’s Terme di Caracalla Circuit. Since that fateful day, Ferrari has garnered over 5,000 world victories on the world’s tracks and roads, becoming a legend in the process.

In order to meet growing market demand, Enzo Ferrari sold the Fiat Group a 50% stake in the company in 1969, a figure that rose to 90% in 1988. Ferrari’s share capital is currently divided as follows: 90% Fiat Group, 10% Piero Ferrari. After the founder passed away in the late 1980s, the shareholders decided to relaunch the struggling company, appointing Luca di Montezemolo as Chairman in 1991.

Under Montezemolo's guidance, Ferrari returned to its former dominance in Formula 1, launched a string of new models and opened up new markets, whilst still retaining the core values from its past. Currently, Ferrari’s list of racing plaudits reads as follows: 15 F1 Drivers’ World titles, 16 F1 Constructors’ World titles, 14 Sports Car Manufacturers’ World titles, 9 victories in the Le Mans 24 Hours, 8 in the Mille Miglia, 7 in the Targa Florio, and 216 in F1 Grand Prix.

The legendary symbol used by Ferrari has heroic origins. It was first adopted as a personal emblem by a highly decorated Italian World War I pilot, Francesco Baracca, who had it painted on the fuselage of his aircraft.

At the end of the war, Baracca’s parents allowed Enzo Ferrari to use the Cavallino Rampante (Prancing Horse) symbol. He adopted it as the logo for his racing Scuderia, placing it on a yellow shield in honour of his hometown, Modena, and topping it with the Italian tricolour. The classic Ferrari red, instead, was the colour assigned by the International Automobile Federation to Italian grand prix cars in the early years of the 20th century, but soon became a distinctive trait of the Maranello-born vehicles.

Photo Credits

Afshin Behnia, http://s.petrolicious.com/quick-takes/2013/jonathan-giacobazzi/jonathan-giacobazzi-02.jpg

© All rights reserved.

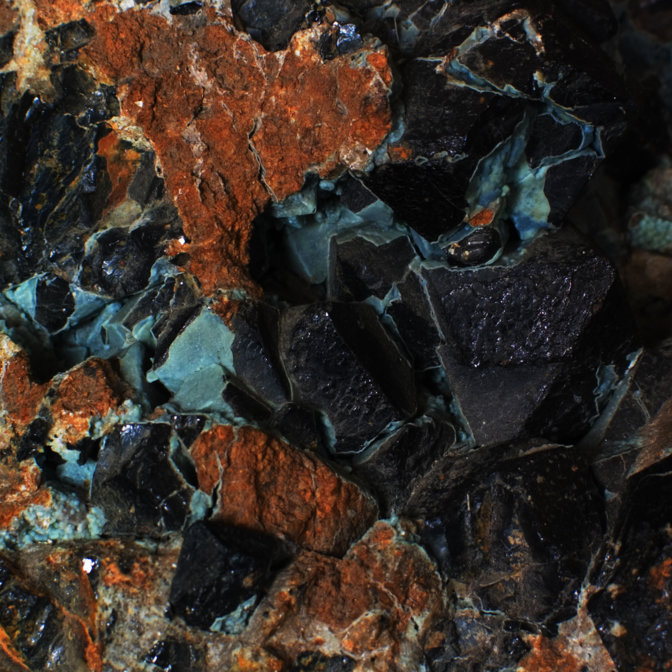

Black gold

Black gold

It is widely known that Piedmont is an absolute Mecca for white-truffle lovers, but not many are aware that Emilia Romagna and the province of Modena, in particular, are also ideal lands for the growth of truffles.The Appennini Modenesi offer a combination of soil, plant species and weather conditions that enable the growth of both white and black truffles.

Truffle hunting is a job done by few, as the locations where truffles are abundant are kept a secret and passed down generation after generation.

The search is carried out with the help of trained dogs. If you have never seen a truffle hunter at work, Modena Tartufi, a family-run company with a fourth-generation truffle hunter at its lead, offers the possibility to participate in outings on its lands.

Any suggestions?